*We are now accepting new clients for the 2026-27 cycle! Sign up here.

X

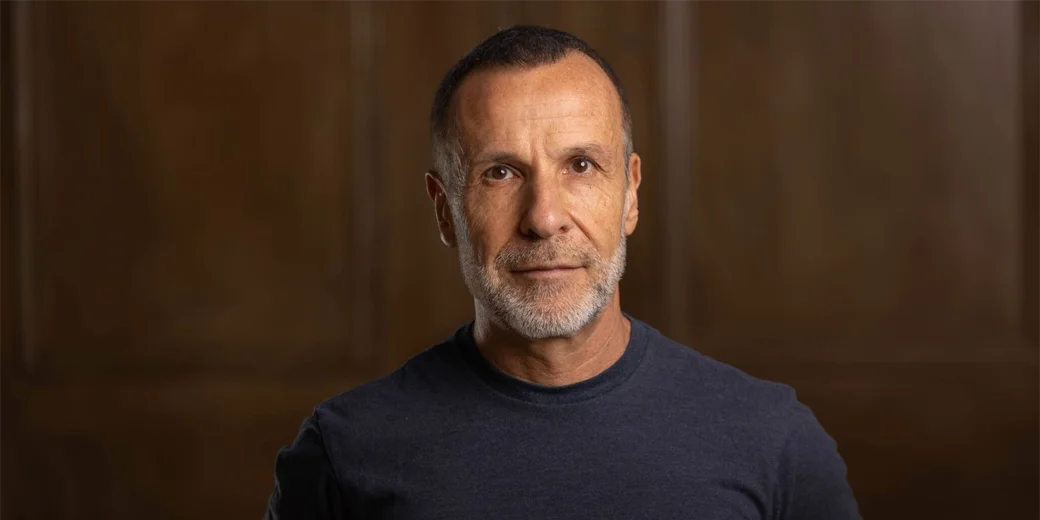

Dr. Anna Lembke is a Stanford University psychiatrist, author of the New York Times best-seller Dopamine Nation, and a featured expert on the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. In this episode, Dr. Lembke discusses the effects of dopamine on our motivation and overall happiness, talks about the degree to which society today sets us up for depression and anxiety and lack of motivation, and offers a concrete (though difficult) remedy.

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, YouTube, SoundCloud, and Google Podcasts.

Mike: Welcome to Status Check with Spivey, where we talk about life, law school, law school admissions, a little bit of everything. I’m your host Mike Spivey, and today I am joined with Dr. Anna Lembke, who is the Chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic at Stanford University. You may recognize the name; she was featured as an expert in the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. She’s written a number of books, the most recent of which is a New York Times best-seller, Dopamine Nation.

And we talk a good deal about dopamine, which is the neurotransmitter of motivation. Here’s how it matters. If you find yourself lying in bed, waking up and playing a video game or watching YouTube videos when you know you should be getting ready for class — or the way she worded it in our interview: if you’re watching lectures from class at 2x speed so you can get back to that video game because you crave playing it — there is something out of balance in your dopamine system that if it’s not addressed, it’s just going to get worse. Your motivation is going to go down. Your desire to study and be involved in life is going to go down.

Dr. Lembke is very busy, she treats patients, so we only have 30 minutes. We spend every bit of that 30 minutes talking about the reward motivation structure, what the detriments are to it, and some of the ways there’s sort of maybe an antidote to some issues people may be having. I hope this is helpful, and without further delay, here’s Dr. Lembke.

Dr. Lembke, it’s great to have you. I’m going to, if I can start off with you in a sort of a curiosity if that’s okay.

Dr. Lembke: Yeah, of course.

Mike: So when we booked this podcast, I let my 35 colleagues at our firm know. One of them immediately responded, “Oh, she terrifies me.” For the record, I’ve read your book, I’ve seen you on Rich Roll, I’ve listened to you on Andrew Huberman. I find you very likeable and not terrifying. Do you get that a lot, or have you never heard that before?

Dr. Lembke: Well, okay first of all did you ask your colleague why, I mean had he seen me and I was scary looking or was it just he heard about it, and it was the notion of it? I’m really curious.

Mike: I know why you terrify him, but I’m curious if, first before I give a leading answer, if you’ve heard this before.

Dr. Lembke: I haven’t heard anybody actually say that to my face. Let me put it to you this way, when I wrote Dopamine Nation, I didn’t think anybody would read it. Why? Because I figured that they would kind of get the gist of my message and then say, “I don’t want to hear that, I don’t want to hear about eliminating pleasures and inviting pain into my life, no way.” But to my surprise, you know, as you know, a lot of people have read it, and it’s really resonated for people. So I hope that I am able to convey what is maybe initially a terrifying message into a really a hopeful and positive message.

Mike: I think that’s right. I think that this notion of — by the way, it is very well received, your book — but this notion of, “Wait, I can’t have chocolate anymore in my life?”

Dr. Lembke: Right.

Mike: “And then the gremlins are going to jump on…”

So our listeners tend to be people who are applying to college, applying to graduate schools. And when I was getting my doctoral degree, this was in the late 90s, it was in goal setting was my research, so it intersected with a little bit of motivation. Back then we — this is so long ago — I believe we thought of dopamine as the neurotransmitter of pleasure. And more recently it’s been much more tilted towards motivation: your ancestors find a strawberry and they are motivated to go back the next day and find the whole bush.

Dr. Lembke: Right.

Mike: And pass on their genes. So how does one in today’s world, where we don’t need to find strawberries but we want to wake up in the morning, how important is our baseline dopamine to waking up motivated, to study when you can turn on the TV or play a video game in bed?

Dr. Lembke: Yeah, so this is really, you know, the heart of the message that I want to convey. And I think the lens of neuroscience is a really good way to do that. And just to communicate that, we are living in a world in which we are surrounded by so many different feel-good substances and behaviors that we’re essentially constantly bombarding our dopamine reward pathways with too much dopamine. And our primitive brains were not evolved for that. Our primitive brains were evolved to approach pleasure and avoid pain, and that’s precisely what’s kept us alive in a world of scarcity — and we no longer live in that world. So, what’s happened is that in order to accommodate the constant things and stuff that we have in our lives, and the constant increases and influxes of dopamine and the reward pathway, is that our brains essentially adapt to that by down-regulating our own dopamine receptors, and our own dopamine transmission.

But importantly, our brains don’t just return to baseline tonic levels of dopamine, we actually plunge below tonic baseline dopamine firing. That means for every pleasure there is a cost, and that cost is essentially some form of pain equal and opposite to pleasure. And that when we get up and smoke a little joint and then play some video games, and then eat some french toast and then you know, roll over to our screens and watch our lectures on double time so that we can get in a few more video games and maybe use some pornography — all of that, in the moment, feels good. But the net effect is actually to push our dopamine firing below baseline levels, such that we are in a dopamine deficit state experiencing the universal symptoms of withdrawal from any addictive substance, which are anxiety, irritability, insomnia, depression, and intrusive compulsive thoughts of wanting to use.

Furthermore, our attention becomes very narrowly focused on our drug of choice such that other things, especially more modest, natural rewards, become uninteresting. Then we need to use not to feel good or get high but just to feel normal. And the reason, Mike, that this is so important is, I see so many young people coming into my office for help with depression and anxiety. And when I ask them how they are spending their days, they essentially tell me that they are online 24/7, playing video games, doing social media, watching YouTube. Or when they are not online, they are smoking a little pot or they are — whatever it is. Essentially, their lifestyle is such that the primary driver of their anxiety and depression is that they are getting too much dopamine.

Mike: Right.

Dr. Lembke: Well, when you are in that, you can’t see it. So one of the first interventions I do with many of these young people is not prescribe them an antidepressant, not even recommend psychotherapy to explore prior trauma. I say, “You know what, let’s cut out your drug of choice for a month.” Because a month is about a minimum amount of time it takes to restore baseline dopamine levels to allow your up-regulation of dopamine so that you’re not constantly craving, so that you’re not constantly anxious and depressed, so that other things seem interesting again.

And I’ve done this experiment, and I call it an experiment in my book again and again. I’ve really become absolutely convinced that this is key not just for my patients but for all of us. And I talk in the book about my own behavioral addictions and how I use it on myself. We don’t even realize that the reason we are anxious, unhappy even miserable is because we are getting too much dopamine. And when we cut that out, what we do is kick into motion our own homeostatic re-regulating and up-regulating mechanisms so that we feel better.

Mike: So I guess I could plug the Twilight series while I plug your book… and hope our listeners will read your book and get what I’m talking about. So I would concur with you that almost all of us have some form of addiction, a way to escape. I have a book coming out in 2022, called Why We Suffer, that eludes to the movie in your book where they had a narcotic pill that was so good at alleviating anxiety, depression… I mean you don’t know good unless you know some bad, and you’ve got to hug your demons at some point. And it’s not always medication — I know that 30 days doesn’t hold true because I’ve read your book, for some people it’s longer, for some people it might be a lifetime of abstinence. But the starting point is 30 days away from the video game on your phone if it’s harming your life. If it creates a short-term, a minute spike of dopamine, is that harmful?

Dr. Lembke: No, and my book isn’t in argument for eliminating all pleasures or even all intoxicants. It’s really an argument for understanding the neural science, appreciating that we live in a “druggifide” world that almost all of us now have some kind of compulsive over-consumption problem that we’re looking to get a handle on. And then laying out essentially a formula for doing that.

And the formula really must begin with abstinence, because when people try to use their willpower to cut back, it’s nearly impossible to do that from a dopamine deficit state. Because the physiologic drive to reassert baseline dopamine levels is incredibly powerful and will have us reaching for our phones, another video game, more pornography, another piece of cake.

But if instead we plan a real trial of abstinence where we are not bombarding our reward pathways, we know we’re going to feel crappy in the first part of it before we feel better. And we give our bodies enough time to restore baseline healthier levels of dopamine, then we can put the self-binding strategies into place. These basically literal and meta-cognitive barriers between ourselves and our drug of choice, such that we can be successful with moderation. Because if we have self-binding strategies in place, we don’t have to only rely on willpower, right? We essentially change our environment in tiny little ways, in an iterative fashion so that we’re not just not constantly consuming and bombarding our reward pathway with dopamine, but we’re not constantly tempted. Maybe we don’t have potato chips in the house, maybe we’ve deleted certain apps from our phone, maybe we’ve restricted our pornography use to certain types of pornography that are not as potent, to maybe only one time per week and other than that we are having sex with our partner. This is the way to think about it. As you know, it’s not all or nothing, and it’s not “never feel good.” But it’s about thinking about what’s really happening in your brain and how can you temper that so that you can enjoy those dopamine hits but not get consumed by them.

Mike: Yeah, the struggle. I always think of the quote from Vincent Felitti I believe his name was — he was the lead researcher on the ACEs study, the Adverse Childhood Experiences — that, “It’s hard to get enough of something that almost works.”

Dr. Lembke: Yes.

Mike: I’ll tell you my addiction, or maybe one of my addictions —

Dr. Lembke: Yeah.

Mike: — is, I can count on one hand trail runs I have finished in the mountains where I’ve been satisfied. I always wish I got faster and farther, and— you can’t see it, but I’m currently in a big boot because for a year I ran on a stress fracture. Even the things that seem like healthy activities can become compulsive or addictive. And it’s from that nature of — the runs were never enough, Dr. Lembke, like I would finish a 5, 7-mile run in the beautiful mountains and say why didn’t I go 9 miles?

Dr. Lembke: It’s a great example. Because I do talk in my book about the importance not just of eliminating pleasure but also intentionally pursuing physically challenging, painful experiences including exercise. But you’re absolutely right, even that can be taken too far. Generally, we think of getting dopamine indirectly through exercise or painful endeavors as a healthier and more enduring source of dopamine. But if you do too much of it, and you take it too far, and for example you run on a stress fracture, it’s obviously not healthy either. And I have also seen in my practice, you know, people who get addicted to exercise. And so again, the intervention there would be a period of abstinence, which by the way is painful, right? I mean, this is the key thing that when we take away our drug, no matter what it is, we’re going to withdraw, right? We experience those psychological and physical symptoms. But if we can just allow ourselves to tolerate it, time in fact will heal that. We will restore baseline homeostasis and then we’ll be able to look more clearly at, “Wow, why was I doing that? And that was really harmful for me and others.” But again, when you’re in it it’s hard to see it. So I would wonder, now that you have some distance from your compulsive running, do you look back at that and say, “Well, that was kind of crazy, I wonder why I kept going”?

Mike: I do, I do look back at it, and I think of the moments — I call them liberation; it’s almost universality or something — I think of the moments where I did run, and I would round a corner and the sun would peek through the trees, I run very early, and I didn’t care about my time. And sometimes, a couple of times, I would just stop and enjoy the sun. And then I wonder why that’s not, at 49 years old why that’s not every run. It’s been six weeks since I’ve been in this boot. So hopefully I’m not going through withdrawal anymore, hopefully I’m somewhat affable. I suspect though it is not in my nature, it’s not going to be a perfect — you talk about this in your book, it’s almost like a bookmark. Your dopamine, for an alcoholic who had severe alcoholism, they can’t take five years off and have one drink. Oftentimes, they’ll take five years off and the relapse will be acute.

Dr. Lembke: Right.

Mike: I have a feeling my running relapse might be acute. So is the solution, Dr. Lembke… let’s say for our listeners, they want to wake up in the morning and be more motivated — and dopamine has a huge role in that — at a baseline level, not at a hitch, not the peak but at baseline level, so that they go to class and stay motivated or get up and exercise in the morning or study for the LSAT or the MCAT. Are there ways to slowly, I’m guessing this is what happened in 300,000 years of homo sapien evolution, where we live in the world slowly getting slow amounts of pleasure that increase our baseline dopamine?

Dr. Lembke: Yeah, I mean you know, we were wired over millions of years of evolution to approach pleasure and avoid pain. That is in us, that is our instinct. The problem is, because we live in this world of overwhelming abundance, that instinct has now gotten us into trouble. So we have to adapt to this new ecosystem using our great big brains, our peripheral cortex, and really orient differently on rewards. And ideally anything that bring us reward kind of quickly and sort of at our command is vulnerable to tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal. And you even have that with your runs and your morning sunrises. So what that tells me is that you could try to find a different source of reward and reinforcement, but there’s also cross-addiction. You know, once we’ve been addicted to something, we can be addicted to something else; it all sort of works from the same pathway.

So I think the key really is to not necessarily look for those kinds of escapist rewards that hit us all at once. But instead to develop a lifestyle in which we invest in the lives we were given, every day, incrementally, in a way that we can find meaning and purpose and not necessarily expect a reward or not necessarily expect to feel good.

I think part of the trap is that we’ve come to decide that, as a culture, we should be feeling good and we should feel happy. But instead, you recognize that life actually really is a struggle and that you know, those moments of grace and moments of happiness still come, but they are often unpredictable. I think if you ask people what is their happiest moment in their lives, it’s often a situation that they didn’t plan for or strive for. It was a serendipitous moment that has to do typically with some deep connection with another human or with a higher power or with nature or a moment of service to others.

So again, I think to kind of try to get away from this idea of, okay how can I reward myself today? Or, how can I arrange my day to sort of modulate my feelings? And instead, really give it over and say, “Well, you know I actually have very little control over how I’m going to feel. I can’t expect that I’m going to feel good. But what’s the next right thing that I can do that will make me feel good about myself as a person, will give me meaning and purpose, will make me feel like I contributed something to the world?”

And if we do that on a daily basis in an iterative fashion, we will feel contented, we will have that feeling that life is worth living. But again, it’s a cumulative, progressive, iterative, small-step kind of process.

Mike: Yeah, yeah. And you’ve mentioned the cross-addictions or the polyaddictions, this is where it gets confusing to me. I’m not a researcher, but I know that we have a good handle on the addictive pathways — or tell me if I’m wrong, please — but pretty much we understand them and they’re the same for any kind of addiction. But we don’t know, and I don’t think we have, and again tell me if I’m wrong, I don’t think we have the E=mc2 equation yet for addiction. Because why does one key fit so perfectly into one lock, alcohol for some people, like I heard you on Rich Roll and he was very candid about that. I’ve read his book. The first drink he had, that was the missing piece of his puzzle. But then he could have some other substance and it not ping off of him at all.

Dr. Lembke: Right, right, and this gets to this key concept of drug of choice. So there’s enormous inter-individual variability. What releases dopamine in your reward pathway might not release as much dopamine in my reward pathway. If you think about that from an evolutionary population perspective, it kind of makes sense. If you’re living in a world of scarcity, you don’t want everybody looking for the same reward, right? You want folks that are biologically designed for different drugs of choice so that collectively as a tribe, we’re getting all the things that we need. So I think that that’s the way to make sense of it. But absolutely, I mean we need to validate that it’s not — we aren’t wired exactly the same, although the basic wiring for processing pain and pleasure is the same even if our drugs of choice differ.

Mike: That’s interesting. Do you think we’ll ever get to a point where we can, and I don’t know if we want to get to this point, but figure out why we are genetically — Anna Lembke is born, don’t give her the Twilight series? Would we want that or no? I mean because, I think, well you — let me guess what you might say. This is — I was a philosophy major, and we’d have to answer questions, “How would Emmanuel Kant answer this question?” Well, I think you would say, well the potency and the availability is so robust in today’s world that even if we identified 14 things you might be prone to be addictive of, there’s 1,000 others out there… “coming to a website soon.”

Dr. Lembke: That’s exactly right. That we are living in an unprecedented time of highly addictive, infinite, ubiquitous, easily accessible, novel substances making even previously you know invulnerable people — because we do have different degrees of vulnerability to the problem of addiction. Some people, you put them in any environment and they’ll become addicted. Other people they would need a whole lot of access and potency to get addicted. But my argument is that today we’re living in a time where we are almost all vulnerable to the problem of addiction.

Mike: Yeah, we had Dr. Maté on our podcast, and I think you and he — and not that it matters, but I — tend to agree that we’re all somehow self-medicating on something, we’re all addicted to something. I think that the difference is, your argument is, you could have the perfect upbringing, the perfect parents —

Dr. Lembke: Right.

Mike: — great life, but because of the society for the first time ever where there’s more leisure time, and I saw that notation about that in 2040 we’re going to have something like eight hours a day.

Dr. Lembke: That’s right.

Mike: Right, is this your belief? And I love that you have a strategy versus a tactic. A tactic would be, here is your SSRI. Strategy is, hug your demons, accept some level of pain, because you also can therefore accept some level of pleasure. Are things like, on the rise right now, and do you suspect that they’re going to keep rising because of this excess in leisure time?

Dr. Lembke: Well, I mean it’s the excess in leisure time, more hours in any given day, more days in any given life, combined with the universal access to high dopamine substances and behaviors combined with the ways that we’re insulated from many physical and psychologically painful experiences. All of which conspire together to give us a dopamine reward pathway that is frantically trying to adapt by down-regulating our own dopamine and other endogenous feel-good chemicals or endocannabinoid, endo opioid, endo serotonin systems such that you know, rates of depression all over the world are going up, especially in rich nations.

Depression has increased worldwide 50% in the last 30 years. If you look at happiness surveys, people in the United States, and around the world but again especially in rich nations, were happier in 2008 than they were in 2018. Rates of alcohol addiction have gone up 85% in women, 50% in older people — these are demographic groups that were previously insulated from problems of alcohol addiction or relatively speaking.

So we’re really seeing a modern epidemic of compulsive overconsumption, addiction, and you know, the smartphone is really just like the everyman example of how we’re all sort of compulsively engaged. I’m so glad that we’re having these conversations, that people are beginning to think about these problems, and I do hope that by looking at it through the lens of neural science as well as, as I do in my book, holding up people in recovery from severe addiction as modern-day prophets for the rest of us, we can cobble together a roadmap for how to live in this new world.

Mike: I know you have something coming up. One final takeaway for our listeners, one final piece of advice?

Dr. Lembke: I think I want to emphasize again, especially for young listeners, if you are unhappy in your life, and/or if you just want to change your behaviors around things that you do too much of and wish you didn’t do, there is a lot of hope. And it’s not sort of an all or nothing proposition. What my book invites you to do is to really do an experiment and gather data. And the key to an experiment is that we need to act, right? We can’t — it’s not just about changing thoughts or changing emotions; we actually need to change our behavior and then experience the emotions and thoughts that follow from that and then interpret them and have that inform next steps.

And so that’s really what I hope young people will do, is to try some things, some things that seem counter-intuitive but which although initially painful and difficult, might actually lead you to a really exciting place.

Mike: I’m going to give this to a doctor friend of mine, I like the way you speak with your patients, I love what you learn from your patients.

Dr. Lembke: Oh thank you.

Mike: And I very much appreciate your time Dr. Lembke.

Dr. Lembke: Oh thank you Mike. It was a great interview, and thanks for the work that you do reaching out to young people especially.

Mike: I appreciate it. And will look forward to seeing you on Netflix again. Bye.

Dr. Lembke: That was good. Bye bye.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Dr. Guy Winch returns to the podcast for a conversation about his new book, Mind Over Grind: How to Break Free When Work Hijacks Your Life. They discuss burnout (especially for those in school or their early career), how society glorifies overworking even when it doesn’t lead to better outcomes (5:53), the difference between rumination and valuable self-analysis (11:02), the question Dr. Winch asks patients who are struggling with work-life balance that you can ask yourself (17:58), how to reduce the stress of the waiting process in admissions and the job search (24:36), and more.

Dr. Winch is a prominent psychologist, speaker, and author whose TED Talks on emotional well-being have over 35 million combined views. He has a podcast with co-host Lori Gottlieb, Dear Therapists. Dr. Winch’s new book, Mind Over Grind: How to Break Free When Work Hijacks Your Life, is out today!

Our last episode with Dr. Winch, “Dr. Guy Winch on Handling Rejection (& Waiting) in Admissions,” is here.

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Mike interviews General David Petraeus, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency and Four-Star General in the United States Army. He is currently a Partner at KKR, Chairman of the KKR Global Institute, and Chairman of KKR Middle East. Prior to joining KKR, General Petraeus served for over 37 years in the U.S. military, culminating in command of U.S. Central Command and command of coalition forces in Afghanistan. Following retirement from the military and after Senate confirmation by a vote of 94-0, he served as Director of the CIA during a period of significant achievements in the global war on terror. General Petraeus graduated with distinction from the U.S. Military Academy and also earned a Ph.D. in international relations and economics from Princeton University.

General Petraeus is currently the Kissinger Fellow at Yale University’s Jackson School. Over the past 20 years, General Petraeus was named one of America’s 25 Best Leaders by U.S. News and World Report, a runner-up for Time magazine’s Person of the Year, the Daily Telegraph Man of the Year, twice a Time 100 selectee, Princeton University’s Madison Medalist, and one of Foreign Policy magazine’s top 100 public intellectuals in three different years. He has also been decorated by 14 foreign countries, and he is believed to be the only person who, while in uniform, threw out the first pitch of a World Series game and did the coin toss for a Super Bowl.

Our discussion centers on leadership at the highest level, early-career leadership, and how to get ahead and succeed in your career. General Petraeus developed four task constructs of leadership based on his vast experience at the highest levels, which can be viewed at Harvard's Belfer Center here. He also references several books on both history and leadership, including:

We talk about how to stand out early in your career in multiple ways, including letters of recommendation and school choice. We end on what truly matters, finding purpose in what you do.

General Petraeus gave us over an hour of his time in his incredibly busy schedule and shared leadership experiences that are truly unique. I hope all of our listeners, so many of whom will become leaders in their careers, have a chance to listen.

-Mike Spivey

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript with timestamps below.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Anna has an in-depth discussion on law school admissions interviews with two Spivey consultants—Sam Parker, who joined Spivey this past fall from her position as Associate Director of Admissions at Harvard Law School, where she personally interviewed over a thousand applicants; and Paula Gluzman, who, in addition to her experience as Assistant Director of Admissions & Financial Aid at both UCLA Law and the University of Washington Law, has assisted hundreds of law school applicants and students in preparing for interviews as a consultant and law school career services professional. You can learn more about Sam here and Paula here.

Paula, Sam, and Anna talk about how important interviews are in the admissions process (9:45), different types of law school interviews (14:15), advice for group interviews (17:05), what qualities applicants should be trying to showcase in interviews (20:01), categories of interview questions and examples of real law school admissions interview questions (26:01), the trickiest law school admissions interview questions (33:41), a formula for answering questions about failures and mistakes (38:14), a step-by-step process for how to prepare for interviews (46:07), common interview mistakes (55:42), advice for attire and presentation (especially for remote interviews) (1:02:20), good and bad questions to ask at the end of an interview (1:06:16), the funniest things we’ve seen applicants do in interviews (1:10:15), what percentage of applicants we’ve found typically do well in interviews (1:10:45), and more.

Links to Status Check episodes mentioned:

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.