*We are now accepting new clients for the 2026-27 cycle! Sign up here.

X

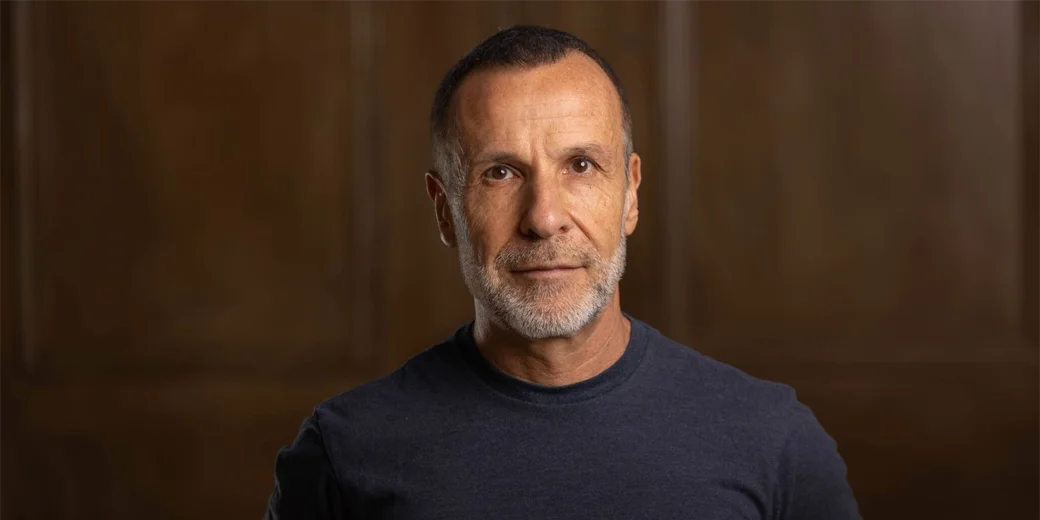

In this podcast, Mike Spivey discusses one of the fundamental difficulties of applying to law school—and how to cope with it. Mike mentions two blog posts in this podcast: the first, about all the different variables that go into law school admissions, can be found here, and the second, about load management days, can be found here.

You can listen to this podcast here or on SoundCloud or Apple Podcasts, or read a transcript below.

Please note that our reservation list for next cycle (2021-2022) is now open.

Hi, this is Mike Spivey of the Spivey Consulting Group. I'm going to give you the time of day, actually — it's 5:30 AM, Wednesday, November 11. I just finished a run. There's two reasons I'm giving you the time of day and the run variable; I'll come back to that at the very end. This podcast is on self-care, the fallacy of reductionism, and something to be said about an N of 1. Incidentally, never use that sentence in a personal statement, because we often talk about not making your personal statements overwrought.

But this is a podcast I've been wanting to do for years. So why have I been wanting to do this for years, and maybe equally importantly, why have I put it off? I put it off because, in almost all of our literature, our blogs, our articles, our podcasts, we focus on — I would almost call it the medicine practice, the clinical practice of admissions, versus the math of admissions. What I mean by that is, admissions is not math; you can never, ever take two plus two equals four. And what I mean by that is, you can't give me your application, and I can't tell you — no one can — that you're going to get into these 20 of 20 schools, or these 18 of 24 schools. Important point to remember, because this is going to bring me to the fallacy of reductionism. What we try to focus on on our podcast is the sort of medicine approach to admissions, which is, "Okay, you know, going into the process, you have a 40% chance at this school, let's turn it into 55% chance." So we can't take 40% and make it 100% — in fact, when we get those inquiry calls, we always politely say, you know, "we can't do that for you" — or, you know, if you're at the 99% chance, so in the medical analogy, if you're, you know, the fittest person on the planet, and you come to us to be your personal trainer, we're not going to take you either, because you're already there. This podcast is not on increasing those percentages. It's on how people decrease their percentages by trying to reduce every component variable, and how in the self-care world, that doesn't work out so well. So again, the fallacy of reductionism.

When I started admissions, I think there was one book in the bookstore, and it was written by this guy, incidentally, with no admissions experience, and he just quoted a bunch of deans of admissions and put them in these little square excerpts. Keep in mind, every school is looking for different things, too, so the book wasn't helpful at all, and then he just wrote about his business school experience. Mercifully, I haven't seen that book in a while. Now there are — literally, and I was playing around with this last night — thousands and thousands of blogs and podcasts on admissions advice. That's just from people who claim to be experts; if you start adding in all the people who just had a good cycle and start giving admissions advice, it's almost unlimited. There are unlimited amounts of information out there. And you can get down to variables that are so ridiculously nuanced that, unfortunately, some people think yielded the outcomes of the applicant, so applicant says, "Hey, I have a 3.5, a 169, and I was just admitted to UVA," and people say, well, you know, "Wow, I want to replicate that. What did you do?" "Well, I visited three times, I spoke to the Dean of Admissions once on the phone, I play the saxophone," etc., etc., and you could go on — I had phone calls the last three hours about these topics. The problem is that, I think, because there's so much information — and incidentally a lot of it is just horrendous — people who apply to law schools, people we interact with, people who visit our firm's blog and our podcasts, are really smart, problem-solving people, so they say, "Okay, admissions is a problem that I can solve. So if I just find all" — again, mathematics — "If I find out every variable and plug it into the equation" — I don't think they say this consciously — "I will get all positive results."

Let me give you a story about how untrue this probably is. Many years ago, my business partner Karen and I, we shared a client. So Karen was the Director of Admissions at Harvard Law School for 12 years, and she had joined me, it was her first year, so we did some joint clients. We had one client, who I can remember where I was when I called her and said, you know, "You applied to 12 schools, and they're all in the top 20, you know, some are in the top 10, and I know your data, I know your application, I know the cycle's data, so you're going to get a lot of waitlists, so just brace yourself." And I can remember, you know, where I was standing; I was standing behind a Target. I was going to go in there and buy my three typical 5 Hour Energies of the day to get me through the day. But I felt the need to let her know that it was going to be a long cycle before I started my day, because I knew she just submitted. Long story slightly shorter, she gets into something like 11 of the 12 schools right off the bat. Incidentally, by right off the bat, I don't mean, like, that week, I just mean that she wasn't waitlisted, she was admitted, straight up admitted to 11 of the 12 schools. So, we were fascinated because this was not the outcome we predicted, and between the two of us, Karen and I, we have about 40 years admissions experience. So you know, we're pretty good often at predicting outcomes. So we went back in there, and we read her application, and we read it again. To this day, I cannot tell you why she went 11 of 12. I know she had a differentiated and kind of clever personal statement. I know she had some good softs. But I personally, nor can anyone at my firm, reduce every component variable that would yield the results that she had. So that would be, again, the fallacy of reductionism, because we try — man, when people have home-run results, we go in there, and we try to figure out, you know, can we replicate, obviously not the exact wording, but can we replicate the strategy?

There's a scientist I'm quite fond of; he's a longevity expert, and I would rather live longer than shorter. His name is David Sinclair. I remember him saying once in one of his podcasts, we hardly know how one atom interacts with another atom, so science is very tough. My point is this. In admissions, sometimes we don't know why one variable that's minor bounces off another variable that's minor, that creates sort of a synergistic effect that causes someone — and this is all you want to do, is — [to] get more eyes on your file more often. If they're not interested in you, they're not taking the time to pull your application file. So there's probably 15 or 20 variables that we know as a firm will get people to look at your file. And we did a blog on that. So rather than me just taking up time in this podcast, we will link that blog, you can look at what those 15-20 variables are. There's probably 1,000 variables that also, on any given day, may or probably may not hit that dean of admission on that day.

I remember one of my first jobs in admissions, my boss was super data-centric, particularly very data-centric early in the cycle, and all that means is, you know, we would find candidates that we adored late cycle below our medians and admit them, but early cycle, generally, it was people that helped our medians. So one day, very beginning of the cycle, I see that we admitted someone with an LSAT well below our median, and it wasn't phenotypic of what we would do in admissions at the time at that time of year. So I got intrigued, and I pulled that person's file. Turned out, they had one line on their resume, it was a powerful line, they were a former Olympic skier. And what did my boss who admitted them have a huge passion in life for? Skiing. Again, you know, you can't replicate that data point, you can't just start putting things in resumes that hopefully the dean of admission has a passion for. But the right variable bounced off the other right variable at the right time.

Which is going to now sort of get me to the N of 1 part of this, which also gets me to the self-care. You are an N of 1, and there's never in science, math, anything, including admissions — particularly including admissions, because I hate these predicting websites. We could put one up on my firm and get a lot of traffic, and we have a lot more data than I think the ones that are out there, but it's misleading traffic because it doesn't capture anything but "this was my LSAT, this was my score, this is the school I got into." But does that capture my friend Justin Ishbia? Again, I love using him as an example because I have carte blanche permission to use his name. He applied, non-URM,152 LSAT, to Vanderbilt when I was at Vanderbilt. He was the last person admitted off the waitlist — we admitted him either, you know, two days before orientation, or the day before orientation, or quite possibly even the morning of orientation. And there's nothing possible in a predictor that would explain why we admitted him. To this day, I'm not even sure I could explain why I admitted him that day. I just always remembered his visit and the sincerity with which he addressed his LSAT score and his career ambitions, and there was nothing phony about it. And all cycle long I had him in the back of my head. But again, these aren't variables you could ever figure out online and say, "Oh, I saw someone with a 152 non-URM admitted at Vanderbilt, you know, I bet you they're special interest" — he was not — you know, or, "I bet you there was something in there amazing," and there wasn't, it was just a sincere conversation one day. Again, two variables hitting each other at the right time at the right moment. And he was an N of 1, a sample size of 1, because he stood out, but you couldn't replicate how he stood out.

So now let me get the self-care, because I'm already going a little bit too long. The self-care that I'm getting at is — I see more and more every cycle, and this is a tough cycle inarguably — the problematic part is, more than ever before, people look at other people's results. And it's almost always going to seem like this: "Oh my goodness, look at these waves of admits; all these people are getting admitted, and I haven't heard from my school." Except so many other people — trust me because they're sending me direct messages, emails, Twitter messages, etc., or you just see it on online — so many other people are having that exact same thought too. "I submitted my applications in September, and it's December, and I haven't heard from a single school, so I must be doomed." That is the fallacy of reductionism, because you're trying to see why all these other people got in, and you're not looking at yourself as an N of 1. I can't tell you how many times over the last 6, 7, 8, 9 years, people who haven't heard in September, haven't heard in October, haven't heard in November, haven't heard in December, and next thing you know, they get this wave of January admits. I'm horrible at timing, by the way, at predicting — I'm generally pretty good at predicting whether someone will get into a school eventually or not, [but] horrible at timing, because again, there's just variables bouncing around that admissions office that you don't know of.

So self-care, what can you do? Number one, I wish people would get away from these prediction websites. Unless ETS and LSAC were to take every single data point and put them in a matrix — which, incidentally, would still defy the understatement of the N of 1 — you're really looking at a tiny self-selecting fraction of the applicant pool that's giving you almost no good information and stressing you out. So the first thing you should do is get away, I think, as much as you can from prediction modeling.

The second thing is, and I'll link this blog — I have a motivational blog, too, called Spivey Blog, and there's one I wrote on "load management day," because I found myself too stressed out by constantly being on social media, constantly getting messages, constantly having to read, you know, stories about myself online. So I give myself what's called a "load management day" where I literally delete every device from my phone that connects me to the social media world. Obviously, I don't delete my phone, because I have to be on the grid, but I don't check things for a day. If you could give yourself two load management days a week, your cycle would be much less stressful. Believe it or not, you probably might even, at the margins, have better results because you're not trying to do all this emulation stuff, January, February, March, April, when you're seeing people get off the waitlist and you're trying to emulate them by just spamming schools with phone calls — that's a podcast for a different day.

I mentioned the time of morning that I just ran not so much because I'm super proud it's 5:30 AM or I'm super proud that I ran, but what helps me is routine. So when I get up really early, and I get exercise in really early, and then I get my most stressful work assignments done really early, that routine is very good for my self-care. Having things that get me away from work — I won't give myself an example; I'm not going to talk about like, you know, things I do for fun, which are really boring, reading and writing — my COO Anna Hicks, who I probably call eight times a day, she plays Dungeons and Dragons. She might edit this part out of the podcast. She plays Dungeons and Dragons, I don't know, twice a week, maybe. I actually don't know; she doesn't often just tell me when she's playing, but I try to figure it out in my head so that I won't call her during that three-hour period — because everyone needs to get away.

Look, if you go work in biglaw, mid law, a company, the demands placed on you are going to be so enormous time-wise. Hopefully you'll think back to this podcast and you'll say, I remember that guy saying that, and now I know why when I sent him a direct message I usually only get a two sentence reply, because he's getting 300 a day — that's going to be your life. So don't make it your life now. That's another sort of self-care part. You don't have to be on the grid. Someone checked their Georgetown status checker — this was years ago — like 1,500 times in one day, and then some other applicant figured out how many seconds that was per waking minute. You know, it's like every 47 seconds they were checking their Georgetown says checker, which incidentally, schools can see that. Getting away. Having hobbies. You know, I'll let you pick your hobbies, of course, it's none of my business.

I'm going to mention one more thing. You can also embrace the stress, oddly as that sounds. There's an author Kelly McGonigal, who I'm sort of very remotely connected with. Somehow we became friends on Facebook, and once a year, usually it's me, I'll send her a message and I'll say, "How did you finish your three books? I'm still stuck on book number one," and, you know, she'll give me a little bit of advice. She wrote a wonderful book I highly recommend — I rarely recommend books to law students because of the amount of reading you're going to have to do — it's called The Upside of Stress. Stress is not always our enemy, particularly when you can make a challenge an opportunity and learn from it, and this book is wonderfully about that. What is the law school admissions process if not a challenge? And if it seems challenging now, just wait until this summer when you're on waitlists. There's going to be stress; there's going to be challenge. You can embrace it in the right kind of way. Again, I would recommend that book, The Upside of Stress by Kelly McGonigal. Disclaimer, I get zero kickback or royalties from it. I mean, she has no idea I'm even mentioning this. It was just a book that I read that I really appreciated.

I hope this was helpful. It was longer than I thought it would be, and I hope it makes sense. Again, generally our podcasts are, "do this variable, do this variable" — and we'll link that; I'm going to link to load management one, I'm going to link the one on the variables that matter the most — and if you do these things, it'll increase your chances. What I'm trying to talk about now are the people they get so — understandably so — so into the admissions process, that they decrease their chances by trying to capture ahold of variables that we're not even sure on any given day are really impactful or not. Self-care, the fallacy of reductionism, and honest to goodness, there is something to be said for an N of 1. This was Mike Spivey at the Spivey Consulting Group.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Dr. Guy Winch returns to the podcast for a conversation about his new book, Mind Over Grind: How to Break Free When Work Hijacks Your Life. They discuss burnout (especially for those in school or their early career), how society glorifies overworking even when it doesn’t lead to better outcomes (5:53), the difference between rumination and valuable self-analysis (11:02), the question Dr. Winch asks patients who are struggling with work-life balance that you can ask yourself (17:58), how to reduce the stress of the waiting process in admissions and the job search (24:36), and more.

Dr. Winch is a prominent psychologist, speaker, and author whose TED Talks on emotional well-being have over 35 million combined views. He has a podcast with co-host Lori Gottlieb, Dear Therapists. Dr. Winch’s new book, Mind Over Grind: How to Break Free When Work Hijacks Your Life, is out today!

Our last episode with Dr. Winch, “Dr. Guy Winch on Handling Rejection (& Waiting) in Admissions,” is here.

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Mike interviews General David Petraeus, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency and Four-Star General in the United States Army. He is currently a Partner at KKR, Chairman of the KKR Global Institute, and Chairman of KKR Middle East. Prior to joining KKR, General Petraeus served for over 37 years in the U.S. military, culminating in command of U.S. Central Command and command of coalition forces in Afghanistan. Following retirement from the military and after Senate confirmation by a vote of 94-0, he served as Director of the CIA during a period of significant achievements in the global war on terror. General Petraeus graduated with distinction from the U.S. Military Academy and also earned a Ph.D. in international relations and economics from Princeton University.

General Petraeus is currently the Kissinger Fellow at Yale University’s Jackson School. Over the past 20 years, General Petraeus was named one of America’s 25 Best Leaders by U.S. News and World Report, a runner-up for Time magazine’s Person of the Year, the Daily Telegraph Man of the Year, twice a Time 100 selectee, Princeton University’s Madison Medalist, and one of Foreign Policy magazine’s top 100 public intellectuals in three different years. He has also been decorated by 14 foreign countries, and he is believed to be the only person who, while in uniform, threw out the first pitch of a World Series game and did the coin toss for a Super Bowl.

Our discussion centers on leadership at the highest level, early-career leadership, and how to get ahead and succeed in your career. General Petraeus developed four task constructs of leadership based on his vast experience at the highest levels, which can be viewed at Harvard's Belfer Center here. He also references several books on both history and leadership, including:

We talk about how to stand out early in your career in multiple ways, including letters of recommendation and school choice. We end on what truly matters, finding purpose in what you do.

General Petraeus gave us over an hour of his time in his incredibly busy schedule and shared leadership experiences that are truly unique. I hope all of our listeners, so many of whom will become leaders in their careers, have a chance to listen.

-Mike Spivey

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript with timestamps below.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Anna has an in-depth discussion on law school admissions interviews with two Spivey consultants—Sam Parker, who joined Spivey this past fall from her position as Associate Director of Admissions at Harvard Law School, where she personally interviewed over a thousand applicants; and Paula Gluzman, who, in addition to her experience as Assistant Director of Admissions & Financial Aid at both UCLA Law and the University of Washington Law, has assisted hundreds of law school applicants and students in preparing for interviews as a consultant and law school career services professional. You can learn more about Sam here and Paula here.

Paula, Sam, and Anna talk about how important interviews are in the admissions process (9:45), different types of law school interviews (14:15), advice for group interviews (17:05), what qualities applicants should be trying to showcase in interviews (20:01), categories of interview questions and examples of real law school admissions interview questions (26:01), the trickiest law school admissions interview questions (33:41), a formula for answering questions about failures and mistakes (38:14), a step-by-step process for how to prepare for interviews (46:07), common interview mistakes (55:42), advice for attire and presentation (especially for remote interviews) (1:02:20), good and bad questions to ask at the end of an interview (1:06:16), the funniest things we’ve seen applicants do in interviews (1:10:15), what percentage of applicants we’ve found typically do well in interviews (1:10:45), and more.

Links to Status Check episodes mentioned:

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.