*We are now accepting new clients for the 2026-27 cycle! Sign up here.

X

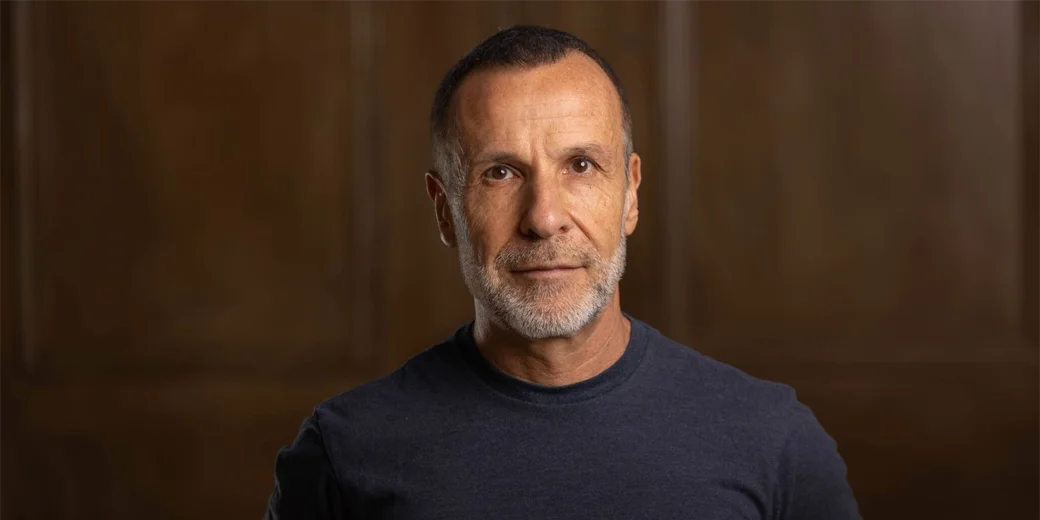

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Mike interviews Miller Leonard, author of How to Get a Job After Law School: The Job Won’t Find You (free online here), on the lessons he’s learned about networking and getting a legal job in his 25+ years as an attorney. Throughout his career, Miller has been a prosecutor, public defender, legal aid attorney, Special Assistant U.S. Attorney, and Municipal Judge, and he regularly shares legal employment and practice advice for his 40,000+ followers on LinkedIn.

Miller discusses concrete steps anyone can take to network with lawyers in their field of choice (8:03), the jarring dynamic shift that happens when high performers go from being students to job-seekers (17:01), networking advice for introverts (19:34), predictions for the future of the legal hiring market and AI (25:16), what law schools are doing right (31:35) and wrong (38:06), overlooked opportunities for new law school grads (42:22), and more.

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.

Mike Spivey: Welcome to Status Check with Spivey, where we talk about life, law school, law school admissions, a little bit of everything. Law school would be our category. We’re talking about how to get a job after law school. I’m with Miller Leonard, who has a really significant presence on LinkedIn. And he gained that presence by giving free advice and then writing a free book or booklet on how to get a job. Miller has an incredibly interesting background in trying murder cases. He’s been a municipal judge. He’s been a special assistant to the United States attorney. He’s currently assistant DA in Chattanooga, so I tried to hit him up with some cool stories.

But we talked mostly not about his career, but in this ever changing employment world, and boy is it changing, in this ever condensed paced of firms looking at people earlier, and 85 to 90% of jobs not coming through OCI but rather getting out there and meeting people, networking, building relationships, learning what different areas of the law are. And putting those front and center, or in front of people who can hire. How to talk to people, how to connect, how to build your relationship.

That’s the primary conversation we have. I hope it’s value added for students and even 0Ls now who have to think about looking at jobs. Without further delay, here’s Miller and me.

I’m here with Miller Leonard. How goes it, Miller? It’s been a while for us to schedule this. You’re a busy guy, and I’m a little busy, too.

[1:32] Miller Leonard: Yes, it’s going well. And it has been a while, but I think our schedules have been passing each other like ships in the night. So I’m glad we could meet up and talk about jobs for law students and how they can get them.

Mike: So, I mean, just to give a preview of your life and my life—and I think sometimes you have people going into law school, these things sound glamorous, but I can almost assure you they’re not—I wake up at 3:00 AM every morning because my schedule’s so demanding. Yes, that does give me a little flexibility. And you had something like last Friday when we were going to try and do this, 132 dockets? 152? What was the number?

Miller: Last week was a Sessions Court week. And it’s probably on every Sessions Court week, I would say, that we’ll have independently 150 to 175 cases. That’s a normal Sessions week. A heavy Sessions week might be a couple hundred cases.

Mike: A couple hundred. And how long? Just give the audience a feel for what that means. You’re an assistant DA; you’ve been a judge, right?

Miller: I have, yes.

Mike: And you’ve run a law firm.

Miller: I have.

Mike: All in the same courtroom, basically.

Miller: So, my career spans three states. I started off in Missouri, then I was Colorado. In Colorado, that’s where I was a judge, but I also had a private practice. I was a judge in the city of Arvada, which is think 120,000 people. And now I’m in Chattanooga as an assistant district attorney. And in Chattanooga, in the criminal courts, you will have two separate types of courtrooms. On the second floor, you have Sessions Courts. That’s where cases will originate if they’re not directly presented to the grand jury. Every other week, if you’re a line attorney in our office, you will rotate into Sessions Court.

And we vertically prosecute. So, Sessions Court is anything from public intoxication to first-degree murder. It just depends on what you’re picking up that day. We’ll divide our docket based on dates. So, I’m the first 10 days of the month, and my two other colleagues will carry their respective 10-day dates. And in Sessions Court, you’ll have, Monday through Friday, you’ll have morning court. We will have afternoon court Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and not Thursday and Friday, because we have Veterans Court on Thursday, and Friday afternoons are just open.

Mike: Can you humor us before we get going on how to get a job out of a law school? Is there an outlandish story anywhere from, you mentioned murder to public intoxication, that you can talk about—obviously, there are some you can’t talk about—that just stands out in your career as, “I can’t believe I’m sitting here listening to this story”?

Miller: One of the things about working in the criminal side of the fence is that the outlandish becomes normal and regular. And so, basically, if you can think about it, it comes into court. You should Google Wayne DuMond.

Mike: I’m going to guess this is some murder. Horrible.

Miller: It was a bad murder, but he’s got quite the backstory.

Mike: We’ll Google it the second we get off this podcast. Thanks. You’ve tried it all, but you’ve done probably many multiple murder cases.

Miller: I’ve done everything except a capital case. I haven’t done a capital case, either as defense attorney or prosecutor.

[4:32] Mike: So why your interest—and I think it relates to your first page on your book, but I could be wrong—you spend so much time helping law school students get jobs. What’s the passion for that?

Miller: So I graduated law school in 1998, which is a long time ago now, and one of my distinct memories of law school, one of my only memories of law school that stands out, is walking across the lawn. I think I’d gone in to return something for the last day of school. I’m walking across the lawn, there’s a couple guys playing catch with a football, and I don’t have a job. I think they had jobs. To give you some context, I had worked all through law school. I had worked at two different private law firms. I had interned at the Missouri State Public Defenders Appellate and Post-Conviction Western District Office. So I had internships as well, but none of those internships were leading to jobs.

1998 was a hard year for graduates. It was just a stuck market. Nobody was leaving government jobs. Private jobs were hard to come by, so I graduated without a job. And I remember what that was like. And if I look back, I also think to myself as somebody now who’s been practicing for 25 years or so, there’s a lot of stuff I didn’t know. Why didn’t I know it? Partially that’s my fault, that I wasn’t as curious or inquisitive, partially it’s because I didn’t know what I didn’t know, and partially it’s because the options to learn weren’t presented. And I decided that through LinkedIn, I could try and help educate students about the legal profession, which I think is very opaque. I call it a hidden job market because most of the good jobs in the law are really hidden. And you only will discover those jobs by developing a network.

Mike: And we can talk at great length about that and how to stand out. In fact, let’s do, but I couldn’t agree more. I’ll give you an example. I’ve been at three law schools: Vanderbilt, Washington University in St. Louis, and Colorado. I’m very familiar with Golden; I drive past there all the time. That stupid brewing, Coors Brewing thing takes away my phone connectivity. They suck up so much of the airwaves. You get like 15 seconds to 2 minutes of no phone connection and three people dropping. Also from Ooltewah, Tennessee for some time, so we have a lot of overlap.

But when I was in those three law schools, I don’t think once in my many-year career, all the way up to the dean level, running multiple departments, did I hear a single law school talk about, “Hey, when you’re in the real world working for a firm, your number one job is sales.”

Miller: I never heard it once in law school.

Mike: Right, you’re building a book of clients. And it’s not even mentioned. It’s like how people go to medical school, and they don’t have a single class on nutrition. It blows my mind.

Miller: Right.

Mike: So, to your point about not knowing the game, I guess some of it’s on you. 1998, there was the internet. I don’t want to cast any blame on Career Services Offices. They’re overwhelmed. They’re doing resumes and cover letters and traveling, meeting with firms. It’s just the sort of culture of law school to be insular about what’s going on in the real world.

So, how would you, if you’re in a law school now, Miller, if we could put you back in time, knowing the data, knowing the #1 way people get a job is through networking and the #2 way is through job placement notifications that you apply to—which is almost another form of networking; you’re networking with your resume and your cover letter, but then you’re ideally getting to know those people somehow—and, you know, way down around 10%, 20% is OCI… What would you do to stand out? How would you go about your job search and your connecting?

[8:03] Miller: That’s a great question. I’m going to touch on the idea of “a lot of people are getting jobs by sending their resume into a posted job.” My suspicion—I don’t have the data, but here’s my suspicion—that a lot of those people who then end up getting the job, their resume stands out because somebody knows them through their network. And so I think in the law, just to put this out here blankly, I think it’s hard to get a job based off of your resume. Who cares about your resume in the law? Generally, the OCI interviews, what are they looking at? They’re looking at your grades, your LSAT score, your class rank. Because frankly, law school does a really—in some ways good, in some ways bad—but I’ll call it a bad job of distinguishing people. And so the only criteria that an employer can really look at from law school is your grades. Now, I don’t know what law school grades necessarily tell an employer. I think the primary thing they tell a big employer who’s doing OCI is that this person will be devoted to the hours we want you to bill now.

Anybody who’s not in that 10% who gets a job out of OCI—so 89, 90% of people aren’t getting the job out of OCI—they have to figure out how to get a job a different way. And that was something that was never spoken about, at least in my law school. Not that I fault them for it. It just wasn’t talked about. And if I were back in law school now, the first thing that I would do is get my LinkedIn profile built, looking professional, and I would start interacting with lawyers on LinkedIn who are doing what I think I want to do, because the people who are on LinkedIn who are active are a ready source of connection for a law student.

The second thing that I would do if I were a law student, and I wish I would’ve done this when I was in law school, is I would have looked at my adjunct professor list—and there were a lot of adjunct professors at my school, and I think there’s a lot of adjunct professors at almost any law school—and I would figure out what adjunct professors are doing what I want to do, and I would ask them if they could meet with me for a little bit. And I suspect that almost all of them would make time, because that’s why they’re teaching

Mike: Adjuncts get paid hardly nothing.

Miller: Right.

Mike: They’re there because they love teaching and what they’re doing.

Miller: Right, absolutely. They’re there, they want to be there. They like students. They’re invigorated by the students. Here’s the thing that I didn’t know as a student. I don’t necessarily like the term, but I was a first-gen law student, so I didn’t have a parent who was a lawyer. And I didn’t understand that what you’re trying to tap into through networking is somebody else’s contacts. Basically, you’re trying to gain, by proxy, their goodwill. And that’s life in general. That’s how we get ahead.

And once you go talk to somebody who’s doing what you want to do, you will discover, as a law student, that they know exponentially more about what it is you want to do, and have a knowledge base on how you can get started in what you want to do that you didn’t even know existed. And likely your law school isn’t telling you about it either because frankly, they may not know it exists, which again, really isn’t any fault of theirs. Law school exists in a law school world, and the profession exists in its own world, and oftentimes the two never meet.

Those are two easy things you can do. They’re free. And if you spend 15 minutes every day just working on LinkedIn contacts and trying to talk to your adjuncts, in three months, you’ll have more contacts than you know what to do. And if you follow up, then, on those contacts that are given to you, you’re going to find an internship or a job. And I know it because I’ve helped students do this. They find jobs doing this. It works because that’s how you get a job, and it translates also, then—that’s how you get business when you are in private practice.

[11:52] Mike: Not only have I been a Dean of Career Services, I was a Dean of Career Services during the Great Recession, the worst hiring time out of law school in 40, 50, 60 years. 100% agree that the vast majority—and including now, you and I have hit the data—the way the students get jobs is through this word that scares people. Networking.

And I’ve given a lot of talks on this. If you think about it, networking is literally just talking to people. You mentioned it. Dating is networking. Finding your partner is networking, work relationships is networking. We all do it as a lab experiment. All I did for this podcast, Miller, is look at the OCI versus networking versus job posting data and read your bio once, just to see if we could do this without any preparation, which we can, because we’ve been talking our whole lives.

Miller: Right.

Mike: The other thing I would click on is, you mentioned two great ones; there’s one other that’s free. Schools host tons of networking events. Now, to your point, they’re not going to capture 90% of the small firms at their events, but are going to have lots of lawyers there. I’ve been a professional networker at all my law schools—admissions, career services, marketing strategy. My job was to go out and meet with hiring partners, managing partners, applicants. No one really wants to be at those big events, but the second you can elevate that conversation to them talking about their jobs or what they’re passionate about, their lives, they go away from dreading that conversation to sticking onto you.

They don’t want to talk small talk either. They certainly don’t want to talk about the weather, so get them talking about themselves. That’s just networking. It’s Dale Carnegie, How to Make Friends and Influence People in 1945, 101.

Miller: So I’ll give somebody just a layup. If a law student comes to me and says, “Hey, I’m interested in estates, trusts, wills, probate; how do I get into that space?” I would tell them that they need to go onto their state bar website or their local bar website, find the CLE that is going to be the wills, trust, estates and probate year-end or yearly event. Go to it as a law student. You will be the only law student at that event, and you will be able to meet all sorts of practicing lawyers who will be not just impressed, blown away by the fact that as a law student, you’re there. And if you just say hi and talk to them about what they do, you will walk away from that usually two-and-a-half-day event with 10 to 15 lawyers who may be interested in you, because nobody else showed the initiative to show up at their main continuing legal education event.

Mike: Absolutely. When I was a Dean of Career Services, we outsourced everything. Why would I be standing up there talking about how to do a resume when the global hiring partner for Alston & Bird could be doing it for us? She could hire. I can’t.

Miller: Right.

Mike: So, everything that we did in front of students, instead of the mealy-mouth academics talking about it, I had employers coming in and talking about it. And, I mean, you can’t be abusive with people’s time, but the students who override that fear of rejection mechanism and went and talked to the big law hiring partner who’s just presented on how to do a cover letter, I could tell you within one semester which students were going to make it through the Great Recession immediately with jobs. Tell me if I’m wrong. It’s having the ability to approach people without fear, not internalizing this rejection, and it’s also the law of large numbers. You reach out to 100 people, and 10 are going to interview you. And you just need one yes.

Miller: That’s right. That’s exactly it. I think one of the things that most law students have to get over is the fact that—you’re in law school, you’ve been a good student all your life, you are used to getting in the door of schools and having opportunities based on your performance, and there’s this mindset of, “Well, I’m super valuable”—you’re not valuable to a law firm, and that’s hard. So how do you make yourself valuable? You need to show you are willing to put the time, energy, and work in to become valuable to them. And that’ll take a number of years.

And one of the ways you stand out is if you show up at these events where nobody else is. You’re telling them, by your actions, “I’m not relying just on my resume, I have sought out the group that does what I want to do, and I’m willing to put the time in to learn what you’re doing.” Most people won’t do that. Most people I talk to won’t do that. The ones who I talk to and do it all report back to me, “I got a job.”

[16:11] Mike: I’ll give you an example of that. I gave our students, when I was a Dean of Career Services at WashU, I gave them sort of a magic trick, a formula, a hack. And the hack was put in your email—make it concise; lawyers will write very precisely and concisely; it’s not the kind of writing that I get from 0Ls or even 1Ls, 2Ls, 3Ls—make it concise, but make sure you put in, “I will call you in five to seven business days. I will be respectful of your time. I just want to make sure you receive this.” Because what does that do? It makes the person getting the email not want to hit the delete button.

They know they’re getting a phone call five to seven days later, and they don’t want to, like, “I don’t know who you are,” which is awkward, so they keep your name. If I had to guess, Miller, 5% of my students actually did that because they didn’t want to do that seven-day later phone call.

Miller: I think that’s right. Most people won’t follow up. I think it’s hard for a lot of people to understand that there’s a dynamic shift in that they don’t present a value. And it’s not saying they’re not valuable as a person. They are, but they’re making good grades, they’ve always been this good student, and they’ve been told how wonderful they are, and they’re a great person, and then they’re going to enter a profession, and yes, you have a lot of potential, but that’s the key word. You have potential. And how do you show potential? That’s where you have to make yourself stand out.

And I wish I would’ve known that as a law student. I didn’t. I thought it was, well, there’s just going to be a track like everything else. I’ll finish with law school, and it’ll sort of be like finishing undergrad. There’ll be a track that I can go on to getting a good job and then getting business and making partner. And that doesn’t exist.

Mike: My parents, my whole life growing up, all they said was get into a good college. And I took that too much to heart. So, I got into a good college. I’d figure that was my ticket to jobs. And when my lackluster performance—because I was playing sports and with my significant other or my friends, I didn’t really focus on grades. Not once did I go to the Career Services Office, not once during my four years. And it hit me like a ton of bricks when I graduated. “Why don’t I have these jobs lined up? I went to Vanderbilt. It’s a strong school.” Doing nothing will get you nothing. When I was in business school, we had a professor who said something very similar to you: All you bring to the table in your first job is energy and work ethic. That’s it.

Miller: Right. That’s right.

Mike: So show up five minutes early before everyone else. How hard is it to set your alarm five minutes earlier? Show up five minutes early and be, you used the word “high,” I don’t think you mean it like the public intoxicated people in your courtroom.

Miller: No.

Mike: You mean have ebullience, have moxie.

Miller: Yes. I mean, so one of the things that over the summer, when we have interns in the district attorney’s office, I don’t really talk about grades with them. I don’t think anybody talks about what their grades are. But we will look and see, are they eager, and we’re going to look really strongly and see, if they’re given something, are they showing fear, or are they willing to go in and take that risk? Do they ask the questions necessary to get the job done? Are they willing to put the time and energy in? And it’s hard to teach that. The ones who do really well understand, “Yes, I need to make the best grades that I can.” But that doesn’t necessarily translate into being successful as a trial attorney, or a transactional attorney, or whatever it is you’re going to do, because you’re going to have to learn. We do have a trade. You have to learn the trade as a learned trade or a learned profession. But nonetheless, you still have to get hands on and do it to understand it.

[19:34] Mike: So let’s say, for the people out there listening that say, “This is great, I love listening to this, but I’m an introvert, and I don’t know the skills that Miller would be looking for or a mid-size law firm would be looking for,” how do those people present themselves? Like, what’s their approach? You’re introverted. You literally aren’t going to go talk to the presenter after the thing. What would pop out to you? How could they reach out to you and get on your radar?

Miller: Well, introverts, in terms of reaching out to people, are at a somewhat disadvantage. There’s parts of our personality that disadvantage us. So, one thing that I would tell to an introvert is this. If you realize you’re an introvert and reaching out to people and talking to people is hard, then that is part of your personality that you’re going to have to develop a little bit as you go look for a job, because looking for a job requires you to sell yourself. That’s a word we hate, but you have to sell yourself to another person, and we have to communicate to do that.

So figure out how you can comfortably network. Is that by sending a DM to somebody after you have engaged on their LinkedIn profile for a while? Because that’s sort of a soft way to introduce yourself. If you’re an introvert, maybe you like one-on-one conversations more than big group settings. Again, something like a CLE, if you go to, you’re going to like that because a lot of the time you’re going to be actually just listening. You’re going to have the ability to talk to one person at a time and pick them out.

I think that for someone who’s an introvert, the other real skill they should look at is, sit down and determine what area of law do they really think they’re more interested in? If you’re interested in litigation and trial, that’s a distinctly different skillset than transactional. And I’m not saying you can’t be a good trial lawyer if you’re introverted. I think you can, but you would need to determine whether or not you’re going to be so taxed by becoming a trial lawyer that it wears you out, because you’re going to do a lot of speaking, you’re going to do a lot of interacting with people just by the nature of the job.

Mike: What my next book coming out is on psychology. We’ve had a number of psychologists on the podcast because, as you know, and I’ve seen you post about this, mental health, mental wellbeing, addiction, depression, suicidal ideation, all these things are, if you look at all the different fields out there, high on the list for lawyers.

One of the new shining lights of psychology is, well, it’s essentially called exposure therapy. If you’re afraid of flying, what do they do? They put you up on a plane. I actually used to be afraid of flying in my early teens, and I’ve flown on thousands of flights now and I’m 0% afraid. I’ve had an emergency landing where I was comforting the two people next to me. Far cry from the person who couldn’t get on a plane at 12 years old.

So, the exposure therapy. What I would say is, you can be an introvert, but pretend you’re ambiverted—fancy word for you can be extroverted situationally—and get reps. If you don’t want to take Miller for coffee, just reach out to him, message him on LinkedIn, and if he responds, message him again. Get some reps and then try to get up to the going to coffee.

If you get the person talking about themselves, their passions—when I was at WashU and in career services, I went to Greg Schumacher’s office; he was the global hiring partner for Jones Day, the firm that hires the most people on the planet. And when I walked in, all I saw around his huge office, and you can imagine how big this guy’s office, was Notre Dame footballs and basketballs in glass cases. What did we talk about for 45 of the hour? Notre Dame football and basketball, and he did the talking. And I’m an extrovert, so I wanted to talk. But the more he talked, the more likely he was to hire my students.

Miller: Yes, I think that’s right. You have to meet people at what they’re interested in, what their desires are. One thing that came to mind when you’re talking is, you know, for introverts, I get a lot of people who will DM me and say, “Hey, do you have time to talk?” And the reality is no, I don’t. And I sent back to a guy this morning, I was like, “I don’t have time to talk, but if you want to send me a list of questions, I’ll get back to you.” And he sent me a list of questions, and I got back to him, because that took two minutes, or five minutes. Whereas trying to figure out a time to talk was going to be difficult because I don’t know if I’m going to be in court, or sometimes just the time I have, I actually need to be doing trial prep and things like that.

Mike: My old boss at Colorado Law School, Phil Weiser, who’s now the Attorney General for the State of Colorado, he said the same thing. Always have an ask.

Miller: Right.

[23:49] Mike: I can’t stress this enough. If you’re sending a two-page email, they’re not going to read it. If you send Miller Leonard three outlined questions, you’re much more apt to go in there.

Miller: That, and having to ask is key. Talking about it prompted me to think about one of the things that I think that law students forget is that not only do they not know what they don’t know, they don’t even understand the depth of contacts a lot of people have and how, if you can tap into somebody’s contacts or goodwill, the kind of doors they can open.

I mean, I do criminal defense and prosecution work. I’m a prosecutor now, but I’ve done a lot of criminal defense. I know people everywhere who do that. So if I have somebody who I know wants to be a prosecutor or a criminal defense attorney, it’s real easy for me to get on my LinkedIn contact list, which is 40,000-something, and say, “Okay, this person wants to be a criminal defense lawyer in New Mexico. I know this public defender in New Mexico, and I can hook them up in a joint, you know, message and say, ‘Hey, this person wants to do the work you’re doing. I’ve talked to them. I think they’re good fit for the work. How can you help them?’” I’ve seen that time and time for probably hundreds of people I’ve helped with that type of introduction. And they don’t know it exists because they just haven’t had anybody turn the light on in the dark room.

Mike: If you were to make a prediction about the entering job market—right now, 9.3 out of every 10 law students has a job within 10 months. So there’s obviously different levels of jobs, and some are just research assistantships at the same law school that they graduated from, so it obfuscates the numbers a little bit. But those are still—we’ve been on this multi-year glide path upward in better hiring since the pandemic. But you have a few things. You have federal jobs. You know a lot more about this than me; I’m no longer in the Career Services space, although our firm might actually get into this space because we may help schools or students find jobs, because of this prediction I have. But the opportunity for federal employment in the legal sector, I think, is not what it used to be. And that’s created a dearth of jobs that are going to go to other people, which then creates a domino effect all the way down the line. You have what’s eventually going to be recessive economy. There always will be a recessive economy; we just don’t know when it’s going to be.

Miller: Right.

Mike: You have more law students who are flooding the market because there’s been a spike in applications, and then there’s this big thing, artificial intelligence, and I hear mixed things about it. And I’ve never been a lawyer. I went to business school. I took one law school class at Vanderbilt Law School. Our firm’s president who you met, Anna Hicks-Jaco, loves this data point. I got an A+, so my law school GPA is a 4.3. I’m never taking another law school class.

What do you think is going to happen with AI and all those other variables?

[26:35] Miller: AI is interesting. I’m not in any way, shape, or form an expert on it. I think AI will help us do our job in some ways. I think it will add to the job in some areas. I mean, technology, at least on the criminal side, has made a standard DUI case much more complex in terms of the amount of information you have to go through in order to figure out what’s going on. I wonder if AI is going to conversely do some of that to us.

Mike: That already fascinates me. DUI cases are pretty common. When I was in admissions, I think most law school applicants don’t know this, there’s a lot of people that apply to law school with one DUI.

Miller: Oh, yes.

Mike: Now, I don’t think that’s a good thing, but we drew the line at two. One was a mistake, two was a pattern, but there’s a lot of DUIs out there. How was the DUI case pre-technology versus post? What loads of information are you getting?

Miller: So, pre-body-worn video cam or in-car cams, you had a report, and you had the Intoxilyzer result for the BAC or the blood draw. Now you’re going to have the report, the blood alcohol concentration result from a blood draw or an Intoxilyzer, you’re going to have an in-car cam, you’re going to have a body-worn cam, you’ll have the officer’s who responded body-worn cam, in-car cam, you may have jail cam, you may have hospital records you have to get. So even on just a standard DUI, the body-worn cams are going to be probably an hour, hour and 15 minutes. And you’re going to have to go through it, especially if you’re looking for information that might exculpate your client or be useful. So, I think right now, like I’ve got a DUI trial coming up here in December, I think there was 10 or 15 cameras that I’ve got that I got to go through. Some are short, some are long, some seem to have nothing to do with the case. It’s just part of it.

Mike: Yes, that’s interesting. One of the reasons I ask for this specifics, which now makes sense, is AI might be adding to some efficiencies, but it’s actually making some jobs have more work to do in the process.

Miller: Yes. Technology. There’s a murder case that I remember was in our office, and just the sheer number of cameras that tracked the individual was enormous. In fact, one of the presentations that we had at our last DA conference was, how do you take all this electronic data and merge it into something that a jury can use? And the office that was actually presenting this segment of the CLE had digital forensic people who’d come out of a motion picture production background, and they were merging multiple cameras, multiple angles, 911 call audio and syncing it up. And I mean, that job in the criminal justice system didn’t exist 10 years ago.

Mike: Yes.

Miller: You just didn’t have that, that many cameras.

Mike: There’s your example of a pretty interesting case, too.

Miller: They were showing some pretty interesting cases of people on video, and how they zoomed it, and how they would put boxes around each individual. That presents a host of different issues for an attorney, because no one attorney is going to be able to do all of that. Now you’re working with a team much more than the law. One of the things they were talking about was that they weren’t using AI to go in and use the tools that were offered because they didn’t want to have to deal with a hearing in court, explaining to the judge how the video had been manipulated with artificial intelligence.

[29:55] Mike: And you mentioned LinkedIn, and now we’re talking about AI, this is something I’ve been thinking about. I’m always saying to students, “Find me on LinkedIn and connect with me.” And this is another thing about the whole rejection thing that I think law students should be aware of. I have weeks where I’m working just ridiculous, and I’m not going to be able to respond to the LinkedIn message. It’s just going to evaporate. It is nothing against the person—and this is 99.9% of emails or DMs that go out from students to busy professionals that don’t get responded to—it’s not because you did anything wrong in the message. Unless you go on for 16 pages. It’s not you, it’s just how busy the busy professional is.

Here’s my postulation. Because of AI—in a year or two, I don’t know when the event horizon is, but soon—for everyone, now’s the time to do it as a human. Anna and I laugh, the emails we get about our firm that are written by AI are absurd. And we’re going to get so sick of that, we’re going to probably not like emails as much. I think you and I, Miller, are going to get so sick of these AI LinkedIn messages. So if you’re a human being in the world right now, go to LinkedIn and make these connections now and start connecting with people.

Miller: Well, I think that’s true, and I suspect some of these firms will use AI to just weed out emails, in general, from people who they’re not even interested in and have it send out some sort of reply, “Thanks, but no thanks.”

Mike: I think it’s already going on at the firm level, at some firms. I think it’s already going on in undergrad admissions in some cases. I’ve yet to see a law school doing that, but I think you’re right.

In the time we have left, you post a good deal about law schools, what they’re doing well and what they’re not doing well. I can play devil’s advocate. I help lots of law schools, and I think you’re going to be right most of the time, but I still might red team it just because we like to disagree.

Miller: In many respects, if you look at the data, law school’s doing something really well in this sense: If you take the top 100 ranked law schools from the U.S. News and World Report—which I don’t really care about, but that’s a good data point—and you look at their two-year bar success rate, their top 100, maybe it’s like 112, is at 90% or above. So you’re seeing that law schools are doing a pretty good job at getting people past the bar. That number also suggests to me that the real impediment to most people in the bar is just time on the test. If you spend enough time on the test, you’re going to pass it. That should make us all encouraged, because that means they’re doing something decently well in terms of taking a large group of people and getting them a basic understanding of the law, which is necessary.

I think that law schools are overly expensive, and that’s nothing I can solve. Nothing any of us can solve. But if you look at the data from what law school costs 50 years ago to now, it’s just much more expensive. And the expense is so high that anyone, including people with good money, I think, have to sit back and strongly evaluate whether or not law school’s worth it for them.

And that wasn’t the case with somebody who graduated in 1972. They could basically go to a good law school and pay for it without much problem. That to me is a sobering aspect of what’s happened in the law. And I don’t know what we do about that, because I’ll have kids contact me and ask me about that, “Is it worth it?” And I don’t know how to answer. They have to answer that for themselves.

But you had a post, I think, on debt and the fact that you’re paying interest before you even are out of law school. And if you’re graduating with $150,000 of law school debt, you cannot really understand, unless you’re super good with numbers and dealing with them all your life and paying your bills for a long time, what that debt is going to mean for your life for the next 10, 15, 20 years.

Mike: Yes, 100%. I think that you and I have both said something similar. 80% of people applying to law school think they’re going to be in the top 20% of the class.

Miller: Right.

[33:49] Mike: If 20% are getting jobs through OCI—and that’s an inflated number; it’s less than 20%—but if it’s 20%, almost categorically it’s the top of the class. Well then that leaves 80% not. And you see this bimodal distribution, and this big spike at the far right with the jobs which are now $225,000 at, you know, big law firms in big cities. That’s eye candy for an applicant. Even me saying I get up at 3:00 AM—because when I was their age, I’m the same phenotype; “That sounds awesome. I can’t wait to live that life.” Yes, it has its good days, and it has bad days, but, you know, that’s what that spike is. It’s the people getting up at 3:00 AM and billing. I think you put some data on your LinkedIn about how many hours. How many hours is that in a year? Billable hours.

Miller: The super big law firms, my understanding, that pay enormous first-year salary are requiring 2,400 hours. 2,000’s billables, 400, maybe, firm hours. But even if you break that down to 1,800, you’re living at work. And people don’t really understand that. And so here’s another criticism of law school. They sell the law as a prestige industry, and what do they tout? They tout these big law jobs that pay multiple six figures coming out of law school. It’s quote-unquote “prestigious.” Or you’re going to be a clerk or a federal judge. How many kids do you know, “I’m going to go to law school. I’m going to be a federal judge.” No, you’re not. Statistically, you have 0% chance of becoming a federal judge. Zero. You’re just not going to be a federal judge—for most people. Statistically, you’re not going to be a federal court of appeals judge, and you’re sure as heck not going to be a United States Supreme Court judge.

Mike: I’m not a big fan of the rankings either. I was just on Reddit this morning talking about how everyone over-indexes rankings. I’ve yet to meet a hiring partner or a managing partner that can name the top 10 law schools, because they don’t care. I’m guessing, and I’m going to put you on the spot, if I asked you what are the top 10 law schools…

Miller: I have no idea. And not only that, the ones that they would say are #1, to me—now, this is my own maybe bias. Law school’s almost irrelevant to how good of a lawyer you’re going to be. It really tells me nothing other than if you go to a certain school, I know you had to have a certain LSAT. You had to have good grades. So that tells me that you at least know how to study, but I don’t know if that means you’re going to be a good lawyer or not. Especially in what I do, because I’ve known all sorts of super smart people who can’t do trial work. Okay. I mean, it just wasn’t for them. And that’s not really a pro or con on them, it just, that data set of where you went to law school doesn’t necessarily tell me much about whether or not you’re going to be good, especially at what we do. And I understand why a lot of the big firms then will hire from a certain set of people. It sure would tell me somebody’s more likely to bill 2,400 hours for me.

Mike: Right.

Miller: Because they’ve done that kind of work to get to the school that they’re graduating from. I’m not one of these people who wants to take away the hard work, the intelligence that these T14 schools represent. These are smart people who go to these schools, by and large. I mean, I’m sure there’s some outlier on there, but by and large, these are really smart people who have done a lot of work to get where they are. And most of them will continue to put in that good work, and most of them will be relatively successful, however you’re going to try and define that.

Mike: The reason why I brought up rankings is, I think rankings matter in these big clusters that no one sets, because you can’t sell a cluster tier ranking, but you can sell one, two, three, four, which is what US News does, and inappropriately so, I think. There are obviously federal judges, Supreme Court judges, there are a tiny few. If you want to do that or go into academia, I was just going to add, pay attention to rankings.

Miller: If you want to clerk for a federal judge, then by all means, try and go to the highest-ranked school you can. The federal judiciary has become a peerage. It’s the House of Lords. They self-select out of the schools they went to. Now, I’ve done a lot of federal work. I’ve never appeared in front of a federal judge who I thought to myself—and I love federal judges, so I don’t mean this disrespectfully to them—who, when they started talking, I thought to myself, “They’re so intelligent, I don’t understand them.” They use a filter, and this filter is rankings. And it’s just like the old English Peerage system. Your last name is not Mountbatten, so you’re not going to get into our club. Well, you had to have a way to filter out, because not everybody gets to get in the club.

Mike: Yeah.

Miller: That’s what they use it for.

Mike: We should start a podcast, Miller, Outside the House of Lords. But again, if you want to teach at a law school, or—there’s a few unicorn jobs out there.

[38:06] Miller: One of the real problems that law school has is that, unlike medical school, there’s not a residency system or a devoted clinical rotation. And because of that, you have people who go to law school who don’t know what it means to be a lawyer, who are exposed to the academic side of the law. And law schools, all of them are academically focused. Even the ones that are more clinically oriented are still academically focused. The problem that I think can develop is that you can be in law school and say, “I really like this subject,” and you may love the subject and hate practicing law.

And here’s what I would say to the idea that there’s this mental health crisis in the law. Yes, I think there probably is, and there’s a lot of substance abuse issues in the law. There are. And the fundamental problem with the legal profession is that most people who become lawyers should have never become lawyers. And I don’t say that with any sort of elitist sentiment. I don’t say that with the idea that what I do is something that is intellectually so hard, nobody can do it. What I mean is I don’t think they really wanted to do it.

By wanting, I mean they’re not really suited for it. A lot of people, if they expose themselves to what the practice of law is, would say, “I have no desire to do that.” And I get it. 100% get it. And so you see that a lot of these people who come out of law school who really start doing well, especially if they don’t go into like a big law route, who get it, who like it, they’re just really well-suited for it. They knew what it meant. They knew what 2,400 hours looked like, and they were willing to do it.

And if you look at the comments, there’s some comments on one of my posts on hours where people are doubting that people legitimately do the hours. Yes, in any group of people, there are going to be folks who lie. To be human, it means that there’s going to be liars amongst us, but it is wrong and deceptive to tell people and put out there that there are folks in these big firms who actually aren’t doing this type of work, who aren’t billing 2,400 hours or more. There are, just like there are people who run 100 miles. Just because you don’t, can’t, or don’t want to, doesn’t mean there aren’t people who do.

Mike: No, of course. They almost all go to work in the dark and come home in the dark.

Miller: Right. They grind those hours out. And, really, what you’re saying is, “I don’t want to do that, so nobody else can do it.” Wrong. They do. Some people do want to do it. Some people force themselves to do it, and it’s a horrible fit, because we can jam the square peg in the round hole. If you put them with enough force, it will go through, but you’re going to deform that square peg.

Mike: Right.

Miller: And so the more you get yourself exposed to the law, the better off you’re going to be in this profession, because it is, this is my take on it, it’s all grunt work. It’s not a prestige industry. At the end, it’s grunt work, all of it. And if you like the grunt work that’s associated with it, you’ll do really well. If you don’t and it’s a bad fit, and you think it’s going to be the academic exercise, you’re in for a horrible time, because the profession will not, cannot, and is not going to change for you. You will change for it, but not vice versa.

Mike: I mean, you’re giving good advice, try to get exposure. The pushback from our listeners would be, “Well, this is what I want to do, and how will I know if I’m good at or bad at? How will I know if I like it or not unless I do it?” I think that’s also very fair pushback. You can always pivot careers. One of the nice things about a JD is it’s a fungible degree. You can take it to a lot of places.

So I think it’s very fair to say, there’s a lot of people, statistically, who drop out of practicing law, but that doesn’t mean as an individual data point, that’s going to be you listening to this. And you might thrive at it, but to Miller’s point, it’s not just you. Other people post this all the time on LinkedIn, to the extent that you can go watch a case, go to the courtroom, get exposure. Don’t watch Suits. I don’t know what the legal show—I don’t watch legal shows ever.

Miller: I don’t either.

Mike: Ever. Right. But whatever the legal show is of the day, that’s not what it is. Try to get some real exposure. That’ll help. By the way, because we’re an admissions firm, that’ll help you in the admissions process. If you can talk with some sort of intellectual savvy about what lawyers do and knowing what you’re getting into, that law school is going to be much more happy to take you because you’re not going to drop out. That’s good for the law school. The more wherewithal, the better.

Any final advice you have?

[42:22] Miller: I like being a lawyer. It’s been enjoyable. There’s days, of course, where it’s hard, and I don’t like it. I think that a lot of students are drawn to big cities, they’re drawn to big firms, and I get that, and I understand that those are the areas that are getting a lot of attention. But the opportunity in the law, at least statistically, for the average student isn’t going to be there. It’s going to be in some other places. And I think that one of the uncharted territories for a lot of law students are mid to smaller firms or areas where there are less big cities but decent population.

Especially if you like some of the areas of law that serve people and people’s needs, you can find opportunity that other people are overlooking. And that’s what you really want, is to put yourself in the position where you’re finding the opportunity that’s being overlooked, because a lot of people are going to go to DC and a lot of people are going to go to New York City, or LA, or San Francisco. And statistically speaking, then you’re competing against all the other people who went there. And where do you shape up? And I think that a lot of people would have much more enjoyable careers in some of these not-as-glamorous places, and they might be shocked about the kind of money they can make.

Mike: 100%. I don’t know about you. I made $32,000 in my first job.

Miller: $29,500.

Mike: Yes. In my first year founding this firm, we made $38,000. No first jobs are that low these days, so maybe a few in the legal so that you could make good money. So I’m going to do a TL;DR for this podcast. Did you even know what that is?

Miller: No. Uh-uh.

Mike: That’s good. I’m happy for you and your life. Too long to read, so I’ll summarize. I actually think you’re right. I don’t think AI is going to gobble up every job on the planet. I don’t think it’s this thing to be overly scared for. The job market is always going to go up and down. So there will be fluctuations. We’re riding a good wave, and we might ride it for more years. There are going to be jobs at that right side. It’s 20%, it’s steep. There are people that thrive on that right side. If you want that right side of big law, there’s no reason not to. My best friends, in fact, a lot of my close friends are at big law. One of my two mentors is the global M&A chair for Gibson Dunn in big law. Obviously, go for that.

But what I hope this podcast does is it also says there’s no reason not to prepare yourself for the 80% that aren’t in there. And preparing yourself is building your network now, reaching out over email, reaching out over LinkedIn if you can. If you have the wherewithal—not even as a 1L, but as a 0L—once you start getting your admits, shift gears to maybe, “How do I make my network? How do I reach out to people?”

Now, as you know, Miller, law firm hiring has so accelerated to earlier, earlier, earlier. 0Ls are reaching out to law firms. If I’m just admitted to a couple law schools, I am immediately targeting people and, to your book’s point, cities I want to live in, regions I want to live in, people in practice areas I think I might want to do. And I’m reaching out to them to see if I can learn more about what they do for a living.

[45:29] Miller: I’m going to champion my book. I get no money from it. It’s free. It’s a PDF that gets sent out there. The book is a template. And if somebody will take that and just use it as a template or just follow it—and there’s an appendix that has a more condensed networking version—if you do that, or your version of it, you will find a job. And it’s not because I wrote it. This is just something that I learned along the way. It works, and it’s free. And if I could go back in time and have this when I was graduating law school or before I went to law school, I would have loved it. Now, whether or not I would’ve been smart enough to use it, I don’t know, but I hope I would’ve been. And that roadmap is so helpful, because as I used to tell a lot of my criminal defense clients, when they’d ask me, “What’s going on? Why don’t you understand what’s going on in this case?” I’d be like, “Buddy, here’s what’s going on. We’re looking into a dark room. There are no lights on. We have just started to get information. And so, if we get that information, we’re beginning to turn the light on. And where we want to be is to find the light switch so we can turn all the lights on.” And if you get that roadmap, you’re going to first have a flashlight, and eventually you’re going to find the light switch.

Mike: Yes.

Miller: And once you turn the light switch on, it all changes.

Mike: I love it. It’s on my LinkedIn page; we’ll put it in the show notes. The final part I’ll add to that is also, if you stay, it’s hard. It’s challenging. I’ve been there. The more you do in this world, the more failures you’re going to get. You’re going to get some rejections. It’s the same in the admissions process. If you can stay upbeat and ebullient, and high, to use your words—not Golden, Colorado high, but just energetic through the admissions and job process—all my students during the Great Recession who had that attitude, they all got jobs.

Miller: For those people who stay energetic, positive, motivated, who are disciplined—that’s the really key word there, be disciplined, and it will pay off. And just like in your workouts, sometimes you work out and it’s not a good workout, but if you stay disciplined, you’ll see that that line goes up, even if there’s some dips. Those who are disciplined in life and in this profession tend to see their line go up.

Mike: Thank you for making the time, Miller, and for not taking today off. I’ll see you on LinkedIn. We’ll keep connecting.

Miller: All right, thank you so much. You have a good one.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Mike has a conversation with Dr. Nita Farahany—speaker, author, Duke Law Distinguished Professor, and the Founding Director of the Duke Initiative for Science & Society—on the future of artificial intelligence in law school, legal employment, legislation, and our day-to-day lives.

They discuss a wide range of AI-related topics, including how significantly Dr. Farahany expects AI to change our lives (10:43, 23:09), how Dr. Farahany checks for AI-generated content in her classes and her thoughts on AI detector tools (1:26, 5:46), the reason that she bans her students from using AI to help generate papers (plus, the reasons she doesn’t ascribe to) (3:41), predictions for how AI will impact legal employment in both the short term and the long term (7:26), which law students are likely to be successful vs. unsuccessful in an AI future (12:24), whether our technology is spying on us (17:04), cognitive offloading and the idea of “cognitive extinction” (18:59), how AI and technology can take away our free will (24:45) and ways to take it back (27:58), how our cognitive liberties are at stake and what we can do to reclaim them both on an individual level (30:06) and a societal level (35:53), neural implants and sensors and our screenless future (39:27), how to use AI in a way that promotes rather than diminishes critical thinking (44:43), and how much, for what purposes, and with which tools Dr. Farahany uses generative AI herself (47:27).

Among Dr. Farahany’s numerous credentials and accomplishments, she is the author of the 2023 book, The Battle for Your Brain: Defending Your Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology; she has given two TED Talks and spoken at numerous high-profile conferences and forums; she served on the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues from 2010 to 2017; she was President of the International Neuroethics Society from 2019 to 2021; and her scholarship includes work on artificial intelligence, cognitive biometric data privacy issues, and other topics in law and technology, ethics, and neuroscience. She is the Robinson O. Everett Distinguished Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy at Duke University, where she also earned a JD, MA, and PhD in philosophy after completing a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth and a master’s from Harvard, both in biology.

Dr. Farahany’s Substack—featuring her interactive online AI Law & Policy and Advanced Topics in AI Law & Policy courses—is available here. The app she recommends is BePresent. The Status Check episode Mike mentions, with Dr. Judson Brewer, is here.

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Dr. Guy Winch returns to the podcast for a conversation about his new book, Mind Over Grind: How to Break Free When Work Hijacks Your Life. They discuss burnout (especially for those in school or their early career), how society glorifies overworking even when it doesn’t lead to better outcomes (5:53), the difference between rumination and valuable self-analysis (11:02), the question Dr. Winch asks patients who are struggling with work-life balance that you can ask yourself (17:58), how to reduce the stress of the waiting process in admissions and the job search (24:36), and more.

Dr. Winch is a prominent psychologist, speaker, and author whose TED Talks on emotional well-being have over 35 million combined views. He has a podcast with co-host Lori Gottlieb, Dear Therapists. Dr. Winch’s new book, Mind Over Grind: How to Break Free When Work Hijacks Your Life, is out today!

Our last episode with Dr. Winch, “Dr. Guy Winch on Handling Rejection (& Waiting) in Admissions,” is here.

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Mike interviews General David Petraeus, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency and Four-Star General in the United States Army. He is currently a Partner at KKR, Chairman of the KKR Global Institute, and Chairman of KKR Middle East. Prior to joining KKR, General Petraeus served for over 37 years in the U.S. military, culminating in command of U.S. Central Command and command of coalition forces in Afghanistan. Following retirement from the military and after Senate confirmation by a vote of 94-0, he served as Director of the CIA during a period of significant achievements in the global war on terror. General Petraeus graduated with distinction from the U.S. Military Academy and also earned a Ph.D. in international relations and economics from Princeton University.

General Petraeus is currently the Kissinger Fellow at Yale University’s Jackson School. Over the past 20 years, General Petraeus was named one of America’s 25 Best Leaders by U.S. News and World Report, a runner-up for Time magazine’s Person of the Year, the Daily Telegraph Man of the Year, twice a Time 100 selectee, Princeton University’s Madison Medalist, and one of Foreign Policy magazine’s top 100 public intellectuals in three different years. He has also been decorated by 14 foreign countries, and he is believed to be the only person who, while in uniform, threw out the first pitch of a World Series game and did the coin toss for a Super Bowl.

Our discussion centers on leadership at the highest level, early-career leadership, and how to get ahead and succeed in your career. General Petraeus developed four task constructs of leadership based on his vast experience at the highest levels, which can be viewed at Harvard's Belfer Center here. He also references several books on both history and leadership, including:

We talk about how to stand out early in your career in multiple ways, including letters of recommendation and school choice. We end on what truly matters, finding purpose in what you do.

General Petraeus gave us over an hour of his time in his incredibly busy schedule and shared leadership experiences that are truly unique. I hope all of our listeners, so many of whom will become leaders in their careers, have a chance to listen.

-Mike Spivey

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript with timestamps below.