*We are now accepting new clients for the 2026-27 cycle! Sign up here.

X

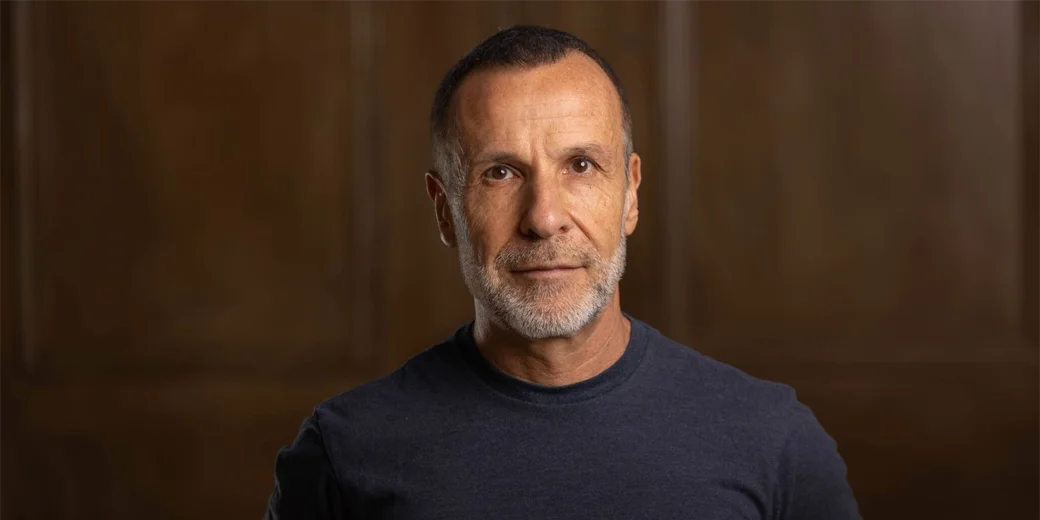

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Anna Hicks-Jaco has a conversation with two of Spivey’s newest consultants—Sam Parker, former Harvard Law Associate Director of Admissions, and Julia Truemper, former Vanderbilt Law Associate Director of Admissions—all about the law school admissions advice that admissions officers won’t give you, discussing insider secrets and debunking myths and common applicant misconceptions.

Over this hour-and-twenty-minute-long episode, three former law school admissions officers talk about the inner workings of law schools’ application review processes (31:50), the true nature of “admissions committees” (33:50), cutoff LSAT scores (23:03, 46:13), what is really meant (and what isn’t) by terms such as “holistic review” (42:50) and “rolling admissions” (32:10), tips for interviews (1:03:16), waitlist advice (1:15:28), what (not) to read into schools’ marketing emails (10:04), which instructions to follow if you get different guidance from a law school’s website vs. an admissions officer vs. on their application instructions on LSAC (14:29), things not to post on Reddit (1:12:07), and much more.

Two other episodes are mentioned in this podcast:

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.

Anna Hicks-Jaco: Hello, and welcome to Status Check with Spivey, where we talk about life, law school, law school admissions, a little bit of everything. I’m Anna Hicks-Jaco, Spivey Consulting’s President, and today I am delighted to be here with two truly wonderful, talented members of our team: Sam Parker, former Associate Director of Admissions at Harvard Law School, and Julia Truemper, former Associate Director of Admissions at Vanderbilt Law School.

Julia and Sam both joined Spivey Consulting this cycle, directly from their jobs at Harvard and Vanderbilt, so up until very, very recently, they were living this life day-to-day. They were working in admissions offices, reading applications, interviewing applicants, managing waitlists, all that good stuff, on an everyday basis.

And today we’re talking about a topic where that recent experience is very relevant. We’re talking about the advice that law school admissions officers won’t give you. There are all sorts of reasons that admissions officers don’t give certain types of advice, and I’m going to ask Julia and Sam a little bit more about those in a moment. But just to be clear right up front, we are not alleging that there’s anything nefarious going on here. It’s a very natural part of the admissions process that the individuals working in admissions aren’t always going to be able to give the maximum amount of information that they theoretically could in any given moment, in any given situation.

Regardless, we’re very excited to share this insider knowledge and strategy with you all. We have a lot to talk about. So let’s get started. Sam, since you’ve been on the podcast once before, do you want to briefly introduce yourself first?

Sam Parker: Sure. My name’s Sam. My background is that I worked at Harvard Law School for almost eight years, absolutely loved my time there, and transitioned over to Spivey right at the beginning of June. So it’s been a whirlwind. I’ve had a blast working with clients, supporting them, and getting their applications in for this cycle, and I’m excited to be sharing some insights from my old job that hopefully will help applicants this cycle and in the future.

Anna: Thanks, Sam. Julia?

Julia Truemper: Hey, I am Julia Truemper. As Anna said, I joined Spivey at the beginning of this cycle from Vanderbilt Law School. I was there as Associate Director of Admissions for about three years. I worked with both JD and LLM programs and did just about everything that you think of an admissions officer doing.

Before that, I was a practicing attorney. I went to law school at Washington University in St. Louis. So I come to this with the perspective of not just a former admissions officer but also a former law student and law school applicant.

[2:30] Anna: That’s a great perspective to be able to have also, because I’m sure you encountered lots of things where you were like, ‘Oh, I wish I’d known this when I was applying,” or, “Wouldn’t this have been interesting to realize when I was applying?”

Julia: Definitely.

Anna: As I mentioned before, I wanted to briefly touch on sort of the reasons that this is the type of advice that admissions officers won’t be giving directly to applicants. So we haven’t gotten into the specifics yet, so we’re not delving super far into any specific situations. Could you both give us a general idea of why the type of information that we’re going to be talking about today isn’t something that admissions officers are talking about as a part of their regular jobs?

Sam: I feel like the #1 reason is that admissions officers just don’t have time to disclose every single thing that’s on their mind that they might want you to know. Especially at the beginning of the cycle, right? Apps come flooding in, and admissions officers start reading at a rapid pace. They’re interviewing applicants, and they’re sitting in committee, or not, and trying to decide who to admit. So they just—they have limited time, and they have to use it efficiently.

The other thing that came to my mind immediately is that admissions officers don’t want to discourage anyone from applying to their school, because they’re looking to get the best applicants and develop the best class that they can. They really are careful about the advice that they give, because they don’t want to discourage anyone from applying, because you never know, that person could have ended up in their class.

Julia: Yeah, I totally agree with all of that. The only other thing that I would add is that it’s really tricky to give advice to applicants, because you don’t want to imply that if you do this one thing, you’re definitely going to get in. If we advise you to, whatever it may be, write your essay in a certain way or submit a certain letter of recommendation, and you don’t get in, you’re going to end up being disappointed if that’s the result.

Sam: Yeah.

Anna: Yeah. Very good point. The point about time, I do think, is sort of the overarching thing. You know, if you want to be full-time advising people on the strategy of law school admissions, come be a consultant, but you probably don’t have time working in an admissions office with all the other things that you have to do.

But yeah, absolutely. The admissions officers don’t want to discourage someone from applying. You know, you sit down with someone for two minutes and they tell you their numbers or something like that, and they say, “Hey, do I have a good shot?” You never want to tell someone, you know, “Oh, you don’t have a great shot,” even if their numbers are well below your range, because you don’t know—that person very well may be the person who gets into your class and is amazing despite not necessarily having the typical numbers.

Okay. So let’s get into the substance. What is our first topic for today?

[4:53] Julia: Well, we thought it would be fun to start off with a little game, one that people are probably familiar with, which is Two Truths and a Lie. So I am going to say three statements, and Sam is going to tell you which one was the lie. And these all have to do with the recruitment process. So:

#1. You should not bring a resume or other handouts to fairs, forums, other recruitment events.

#2. Recruitment events are an opportunity for applicants to stand out and impress admissions officers.

And #3. The goal of attending recruitment events should be to feel out which law schools may be the best academic, personal, or professional fit for you.

Anna: Okay, so if you’re listening at home, pause the episode. Which do you think is the lie? All right, Sam, what’s our answer?

Sam: Drum roll. The lie is that recruitment events are an opportunity for applicants to stand out and/or impress admissions officers. This is not true. This should not be your goal if you’re heading into a recruitment event. Your goal instead should actually be #3, which is you should be feeling out which law schools are the best academic, personal, and professional fit for you.

These events should be giving you a better idea of what schools you might want to apply to, ones that you could see yourself at and be thriving at and be happy at, and ones where you have a good chance of getting in, right? You also want to be a little bit realistic. So that was the lie.

We also just—personally, I strongly disliked when people brought resumes or other handouts to recruitment events, because I had nowhere to put them. Usually, I was floundering around with scraps of paper in my hand. And also it’s just—it’s a little bit odd. I used to get some funny things at recruitment events, like flyers that people had made to promote themselves that would link to websites with kind of interesting or sometimes off-putting information. So it wouldn’t necessarily present an applicant in the best light, so I wouldn’t recommend handing them anything.

[6:56] Anna: Something I hear from admissions officers very frequently when we’re talking about this exact topic is, “If I do remember someone from a forum or fair, it’s almost always for a negative reason.” It’s very, very rarely for a positive reason. And you’re not going to hear someone—I’m imagining now an admissions officer giving that advice to someone at a forum or fair, “No, I’m immediately going to forget you.” Obviously, they’re not going to talk about that kind of thing, but the reality is you’re just meeting with so many people, you’re not going to be able to remember everybody. That’s just not the purpose of these types of events. And so knowing that when you’re going in will help you to get the most that you can out of them and not be spending your time and energy on things that are just not going to help you at all.

Anything to add, Julia?

Julia: No, I think that’s a great piece of advice, and I constantly tell people that you don’t want to be the person they remember. Don’t linger at the table too long, don’t ask too many questions. That’s the kind of thing that really does stand out, and I do remember people from those types of situations. You know, just have a few questions to ask. We’re not judging you. So don’t think that we’re standing there thinking, “Oh, like, I’m looking for a reason not to like this person.” But at the same time, just be conscious of what’s going on. If there’s a line, keep it moving, that sort of thing.

Anna: Yeah. Definitely. All good advice.

Julia: Admissions officers are nice people, and we want you to succeed. We’re not giving you advice with any malicious intent or anything like that. We’re just doing our jobs and trying to be fair in the process.

Sam: I think the important thing to note, too, is, like, an admissions officer’s job during recruitment is to try to sell you on their school and to get anyone and everyone to apply, regardless of how good your chances may be of getting into the school. Schools want to get as many applicants as possible for several reasons, and we’ll talk about this later. But that’s going to include any and all people. So that’s sort of their job with recruitment. It’s not to advise you on which schools might be best for you or what chance you have of getting in, realistically. It’s to get you to apply, point blank.

Julia: Yeah.

Anna: In that type of context, an admissions officer couldn’t—even if they did want to give you an accurate estimate of your chances, they don’t have your application. They have what you can tell them in what, under a minute, about yourself? It’s not the venue where that’s even possible, even if that was the goal.

Julia: Right. And there are a lot of decision makers in this process. As the Associate Director of Admissions, I read applications, but our Dean of Admissions made the final decision. So, I could tell you based on your application, “I think you have a good shot.”

Sam: The other thing is just again, timing, right? Like we used to, for Harvard’s Junior Deferral Program, in our initial launch of the program, we used to give every applicant feedback on their app so that they would have a better chance of putting their best foot forward in a future cycle if they wanted to reapply. We quickly realized how much time that actually takes, and we were like, “We don’t have the capacity for this with our—the seven people on our team that read and review files. This actually just isn’t possible, especially as the program grows.” And then you think about normal admissions—and at least at Harvard, we were getting 8 to 10,000 applications a year. We don’t have time to give every single person that applies feedback. It’s just literally not possible.

[10:04] Anna: We’re talking about the recruitment process and forums and fairs and events and things like that—what about some of these other marketing channels that law schools go through? So, for example, it’s October now. So if you are currently applying to law school, if you’ve signed up for the Candidate Referral Service, you are probably getting a lot of emails from law schools right now. And this is something that I get questions about. I receive questions from, “Oh, I got an email from this law school. Like, I didn’t think I had a shot at this law school. Does this mean that I have a good chance?” What are the pieces of advice here that admissions officers aren’t necessarily telling applicants, but that they should know about these types of outreach and this type of marketing?

Sam: Yeah, so I’ve been getting a lot of questions recently about “special invitations” to recruitment events with particular schools. Some of my clients have been asking me, like, “Does this mean I’m special? Are they particularly interested in me? Do they think I have a good chance of getting in?” Maybe; more likely not. They’re just trying to get as many people at these events as possible. Oftentimes, these invite lists are based on people’s reported LSAT scores. They’re based on your LSAC GPAs. They’re also sometimes based on your address or your identity and what you disclose through the LSAC.

And like we’ve mentioned earlier, law schools are trying to increase their applicant pool as much as possible for several reasons, right? One is that they truly do want to admit the best students. And when you have a larger pool, you’re more likely going to be able to admit a stronger class. They want to increase the diversity of their class, right? They want to make sure they’re admitting a class with people from all different majors and backgrounds and life experiences. So having a bigger pool helps them do that. And then ultimately they’re trying to reduce their final admit rate, right? Because that influences rankings, that influences how people perceive the competitiveness of your school. So if you have more applicants and you’re still admitting the same number of people year after year, your admit rate is going to go down. And that’s going to ultimately help them marketing-wise. So that’s sort of what’s behind-the-scenes happening on why you might be receiving certain outreach emails.

Anna: Yeah. The only thing I will say is that admit rate used to be a bigger part of the rankings than it is now. It’s currently only like 1%, I think, of their methodology. But it’s certainly still something that exists and is in the minds of admissions officers and in admissions offices.

The other thing I’ll say is just that, if you’re thinking about, “I’m trying to attract this group of applicants so that we can choose”—as you were saying, Sam—”just the best possible people for our class,” I would much rather have 50 extra people apply who, realistically, don’t really have much of a shot once I’ve actually read their application, than have one person who really would’ve had a shot and really does have this amazing background but decided, “They don’t seem to be targeting people with my numbers range. They don’t seem to be interested in me, so I’m just not going to apply.” You want that person to apply, and that you are also going to get some folks who don’t necessarily have a great shot.

So yeah, I wouldn’t read too much into those types of marketing emails. Definitely, if you are interested in the school, go check out their webinar, go check out their local event, whatever it is, like, by all means take advantage of those opportunities. But don’t read a whole lot into them apart from just as those opportunities that they are.

Okay, so Julia, I think you have our next topic. Do you want to introduce that?

[13:08] Julia: Yeah. So we’ve talked about how these recruiting events can be a great opportunity to learn more about schools and what schools might be a good fit for you academically, professionally, etc. These recruiting events can also be a great opportunity to learn more about what specific schools are looking for in their application materials. If you attend webinars, virtual information sessions, that sort of thing, you can get a lot of information on what schools are looking for.

So, for example, certain schools want you to list hours per week on your resume for each position, extracurricular activity, that sort of thing. You want to be sure that you are paying attention to what these individual schools want. And these are the kinds of things you can learn from talking with admissions officers and asking questions.

I will say that I would take what you learn in these settings with a grain of salt. Always follow what is actually written on the application. I know when I was at Vanderbilt, sometimes, you know, an admissions officer would say something in a recruiting setting which might not exactly line up with what is on the application. So you do want to be sure that you’re following what is written down. But it can be good to get additional context for the application by talking with admissions officers.

Sam: The only other thing I would add is, as Julia mentioned, make sure you’re reading the application instructions through the LSAC, because those are the official instructions that were submitted by a law school. And those are the ones that you’re going to be held accountable for. It’s not common, but sometimes law schools will have incorrect information or outdated information on their website that may or may not necessarily match the instructions through the LSAC. Treat the ones through the LSAC as final word.

If you do find a discrepancy on a law school’s website, feel free to point that out to them. We got a couple emails when I was at Harvard Law School saying, “Hey, this thing you say online on your FAQ section actually contradicts what the application instruction says. Which one should we follow?” It would be like a great sign for us to be like, “Oh, we need to update the website. Can’t believe we didn’t do that. Thank you so much for that reminder and for pointing that out to us.”

Anna: Yeah. These are good points for sure. If there’s conflicting information, go with what is on the official application on the LSAC website.

The other thing I’ll just touch on is, Julia, you were talking about how sometimes individual admissions officers might say things that are not necessarily representative of what the whole admissions office is looking for. The more subjective a question is, the more there is the possibility of that. So if you’re asking something about just an explicit requirement about their application, you’re probably going to get the right answer. If you ask something that is very subjective and sort of preference-based, the answer that you get might be the preference of that individual admissions officer. And that doesn’t necessarily mean that whole law school is only going to like resumes or personal statements or whatever that align with that preference. And it certainly doesn’t mean that all law schools are going to align with that preference. So I definitely think the point about taking these things with a grain of salt, evaluating them through multiple lenses, I think is a good idea.

We often talk about triangulating your sources when you’re doing research into law school admissions. So if you find one person saying something, see if you can find a couple of other good, reliable sources that can back that up. And then if you are able to find these different sources, especially if they’re from different schools, they’re from different perspectives, then you can feel pretty good about following that piece of advice. Generally, if you find it and the only place you find anyone saying anything remotely like that is in this webinar, then, you know, maybe take it into account for that school, but don’t necessarily change the rest of your application materials for every other school based on this one piece of advice.

So thank you. That was definitely very helpful. So we’ve talked about this recruitment process, and we’ve talked about sort of the marketing events. Let’s get into actually reading applications.

So we’re going from the admissions officer’s side. we’re sitting down now, we actually have these applications in front of us, and we’re evaluating them. Julia, I believe you have another game for this?

[17:07] Julia: I do. And this is a topic I’m very excited to talk about as we’re in the thick of application season. So, Sam: True or False, an applicant should submit the maximum number of essays or addenda for each school they apply to.

Sam: Alright, pause your podcast. What would you guess? Listeners, the answer is, another drum roll...

False. Please don’t do this. And we’ll talk about why, but I wanted to start with a quote from one of our colleagues, actually. Nick, on our team, likes to say, “The thicker the application, the thicker the applicant,” which I thought was really wise and sage advice. No admissions officer out there wants to do more work than they have to. And if you are submitting the maximum number of essays possible, it is most likely going to be overkill. So we’ll talk about a few strategies for avoiding that.

Anna: Yeah, so I’ll just add a few sort of disclaimers, details, coloring in a little bit here. This is obviously going to vary quite a bit from school to school. So some schools, they have basically no optional essays. You’ve got your personal statement and then maybe a spot for an addendum. That school, yeah, you’re probably submitting their one personal statement, and if you have an addendum, then you’re submitting the maximum numbers of essay that they have. That’s totally fine. Don’t start taking this to places that are a little bit—illogical, perhaps.

It’s when you start to get into these schools where they’re like, “Okay, we have these seven prompts, and you can choose as many of them as you want,” no, you do not need to—and it will, in fact, probably hurt you—to submit all seven essays.

Another one is, this is a question that I get that I didn’t think that I would get. People will say, “Oh, I saw this spot for an addendum. Do I need to write an addendum?” and they’re like coming up with ideas for what to write. No, you don’t have to write an addendum. That is very much only for if you have something specific to address there.

The one other thing that I wanted to say is that it’s certainly also not like a linear, literally like on a graph, “The thicker the application, the thicker the applicant.” You know, certainly some applicants have complicated circumstances that they need to explain in an addendum, and that is perfectly appropriate for that specific applicant, and their application would feel like it’s missing something if it didn’t include that lengthy explanation. This is not a one-size-fits-all hard rule.

It is just the very, very broad level idea that I think is helpful for applicants to understand: that admissions officers are not going into reading an application wanting to see the maximum possible information that they have asked for. That’s not, like, the goal; that’s not their overall framework of thinking at all. And in some cases, it’s actually the opposite. I don’t think I’ve ever talked to someone who said, “Oh, we had a two-page limit for this essay and this person only submitted a page and a half, and I held that against them.” I don’t think I’ve ever heard that.

Sam: We can give some specific examples, too. Like at HLS, we used to get applicants who would submit these addenda that were like sometimes 30 pages. Sometimes people would upload their entire senior thesis or their dissertation from their graduate program. Or they would be uploading a “Why Law” essay that we didn’t ask for.

You definitely should submit all required essays. And there are some schools where we would recommend submitting an optional essay. In almost every case, for example, you know, if a school asks you for a “Why X” essay about why you would like to attend their specific institution, why you’re interested in going there, you should be writing that essay if you have the option to do so.

There are also some schools that will allow you to opt into a virtual interview or an interview of some type. And if that is an option, you should almost always be saying yes. You don’t want to give schools an easy way to deny you just because you didn’t opt into that option.

But then that you have to use your best judgment, right? Another example is there’s some schools that have essays specifically about overcoming adversity, and they might even give specific examples of what that means to them, for example, socioeconomic challenges or educational challenges, health issues, disability, immigration status, surviving abuse. If you don’t fall into one of those categories or a similar one, probably in your best interest not to submit an additional essay on that topic, right, because it might show a lack of judgment. So, really use your best judgment.

Julia: Yeah. And I think that’s a theme that comes up a lot just in law school applications in general, use your best judgment.

Sam: More does not necessarily equal better.

Julia: No, not at all.

[21:19] Anna: Definitely. No, I think that component of really evaluating, “Do I have something valuable to say here?” is huge.

The one thing that I will emphasize, even more from what Sam was saying, is that there are some types of optional essays where this is not necessarily the same calculation. So you brought up specifically, like, an optional interview as one where it’s like, okay, you should probably do that. The other one is if a school gives you an opportunity to write an essay about why you are interested in that specific law school. Just to be clear—disclaimers, I’m not at all talking about any one specific law school when I say this—but some of the time when there is that type of a prompt, and some of the time when there is something like an optional interview, it is a litmus test whether you choose to write that essay or whether you choose to do that interview, in and of itself. This is advice that admissions officers aren’t going to give you because, you know, it’s a less valuable litmus test if you tell people this. But write that essay. If you have an opportunity to write an essay about why you are interested in a specific law school, you should write that essay.

I think that this doesn’t even really necessarily conflict with our notion of trying to determine if you have something really valuable to say. Because if you don’t have anything valuable to say about why you’re applying to a specific law school or why you want to go there, then maybe it’s time to reevaluate whether it makes sense for that school to be on your list. Because there should be reasons that you’re interested in going to that law school if you are interested in going to that law school. And there should be reasons beyond, you know, it’s ranked whatever or something of that nature. So I think these essays are something that is really important to do when it’s offered in general. That’s the safest way to go, even if it’s not necessarily that one specific school uses it as that type of litmus test, and two, I think it’s also really, really valuable for applicants to do that research and look into these different schools and figure out, is this a school that I want to attend and why? What opportunities am I excited about?

Sam, do you want to introduce our next topic?

[23:03] Sam: So this is probably the question I got the most as an admissions officer. Julia, you confirm whether this was also true for you, and Anna, too. Do we have cutoff scores? That is the #1 question I used to get. As an admissions officer, I always had to say no, but that’s not 100% accurate. So I did think it was a valuable topic to bring up on this podcast.

At Harvard Law School, did we review every single application that was submitted? Absolutely. Did we review them equally? No, I wouldn’t say that we did. You know, if someone was applying with an LSAT score super far below the lowest score we’d ever admitted at the school, we would look at the app, we would review it, but it was usually reviewed pretty quickly and sent to deny. If you’re getting an LSAT score of a 138, for example, and trying to get into Harvard Law School, statistically speaking, you’re probably not going to get in. So yes, we sort of did have cutoff scores. If you scored low enough, we weren’t going to review your app in the same way.

Julia: Yeah, and I’d say, you know, it’s largely the same at Vanderbilt and I’m sure other law schools as well. And I think we’re going to talk about this more later as far as why we’re looking at those scores, but we’re really thinking about, are you going to be able to do the work at our school? And, unfortunately, if your LSAT score is on the really low end and the same for your GPA, there probably are questions about that. But again, we really do read every single application. It’s just that some might get a little bit more attention than others.

Sam: Absolutely. And you know, when you’re thinking about which schools to apply to, I’ll quote another one of our colleagues at Spivey. Danielle always says, I love this quote of her, she’s like, “It’s important to reach for the stars when you’re thinking about where you want to apply to law school, but you also want to keep both of your feet firmly planted on the ground.” So in other words, it’s important that every applicant out there is applying broadly. You cannot assume that you are going to get in anywhere, especially not in a cycle like the one we’re dealing with now, and you want to make sure you’re giving yourself options, right? So if you’re applying to—let’s say you’re applying to 10 schools—I highly recommend that you’re applying to at least two safety schools, five schools where you know you’re probably going to be competitive or they’re a good target school for you, and then I recommend applying to three reach schools, right? Because you never know. My favorite thing at Harvard Law School, I did admit calls, and I would call people who would immediately scream on the phone and say, like, “I never in a million years would’ve ever thought I would be admitted to a school like Harvard Law School because my numbers, this was such a huge reach school.” So I do always encourage applying to some reach schools, because you truly never know, you might get in. And what a bummer it would’ve been if that person didn’t apply.

If you’re a super splitter, if you’re someone who has significant character and fitness issues or other complicating factors, you might even want to apply even more broadly. It’s not uncommon for some people to be applying to up to 20 law schools just to make sure they’re giving themselves options. So really set up for success by applying broadly and giving yourself options in those categories.

Anna: Yeah, for sure. And if you’re wondering more about assessing your chances, we have a great episode on making your school list. And if you’re wondering more specifically about “safety schools,” we actually have an episode with Danielle all about that topic. And she actually doesn’t like the term “safety school,” specifically, and likes to think of it more as sort of a “backup plan.” So not everybody necessarily is even going to have a safety school. If you don’t have schools where you feel confident that you are going to get in there and that’s a law school you would genuinely want to attend, some people have a different backup. “If I don’t get into this list of schools that I’m going to apply to, then I am going to go do something else. I’m going to go work for a year,” whatever it might be. So I highly recommend that episode with Danielle if you are in the midst of trying to figure out what are some safety schools for me.

And I love the “reach for those stars.” Absolutely. I always say, if you go and you look at any law school where they have a range of the LSAT scores and GPAs that are admitted—so, as opposed to the 25th to the 75th percentile, they have listed the lowest LSAT score that they admitted and the highest LSAT score that they admitted. Look at those ranges. They’re often much, much lower than you would expect for that person who is admitted with the lowest LSAT score of the whole class. That happens every single year at every single school. And it might not be you specifically, but don’t count yourself out. It certainly won’t be you if you don’t apply.

[27:17] Julia: We’re talking a lot about advice that admissions officers want to give you but can’t. And there was one piece of advice that I know as an admissions officer, I was always encouraged to give or told, “This is the one thing you can tell applicants,” which is that it never hurts to get a better LSAT score. So, if you can take the LSAT again, if you think you’re going to have the time to dedicate to studying and improving your score, go ahead and retake it. This especially came up when it came to re-applicants. If you’re submitting largely the same application to us year after year, the one thing you can substantively do to improve your chances is improve your LSAT score. We were very limited in what advice we could give, you know, as far as reviewing your old file and saying what you could have done better, but that’s one thing that we would always point out to applicants.

Sam: Definitely, I will add the caveat from my podcast earlier this cycle, which is if you’re already scoring at the 99th percentile for the LSAT, you really don’t need to retake it. I would highly encourage that you do not retake it. Use your time and energy on the rest of the application components, because at that point, there’s not a ton of improvements that can be made. And law schools might even question why you retook or tried to improve a 99th percentile score.

Julia: Yeah. One of the phrases that I use the most as an admissions officer was “Use your best judgment,” and I think that’s a perfect example of that.

Anna: Yeah. One interesting thing to add to this particular part of the conversation that very much is advice or information that admissions officers will not give you, is that I will say, in some cases, if someone is, for example, put on the waitlist at a school… there are certainly cases where someone is put on the waitlist at a school where the people who are putting them on that waitlist know for a fact that they will not be admitted unless they get a higher LSAT score. And maybe they’ve signed up for that other LSAT, maybe they’ve talked to admissions and they’ve told them that they were interested in taking another LSAT. Maybe the admissions officer just really, really likes the person and is hoping that they will get the waitlist and take the LSAT again. There are those cases where really, like, the one missing component of your application—they love everything else about you—and that LSAT score just gives them the concern where, “I don’t know if this person is going to be academically successful at my law school.” And that’s the last thing any admissions officer wants to do, is to admit someone and bring them in, and then they are not able to do well at the law school, and they have to leave or something like that. So that’s the other component I will add that isn’t necessarily going to ever be said to an applicant, but I think is true in some cases.

Sam: Definitely. I remember sitting in committee last year and our team literally saying, “Oh, we really want to admit this candidate, but the LSAT is really holding them back. Let’s wait and see if they retake it, and by our next committee, maybe we’ll be able to admit them off the waitlist.” I also remember last year reviewing an app, and I just loved everything about this application, and the one thing really holding it back was the LSAT score. And the biggest bummer was that this applicant had only taken the LSAT once, and they didn’t attempt to take it even one more time to get a slightly higher score, and we ultimately ended up denying the applicant for that reason. But it just goes to show that, retake it one more time. Sometimes that can make all the difference in getting that admit versus that denied decision.

Anna: Yeah, and I would say this is much more likely to be the case if you are in that well below the 25th percentile type of realm. Or certainly, you’re not necessarily that exceptional applicant, but if you are someone who’s considering retaking the LSAT, and that would take you from below their median to above their median, that’s certainly always going to make a positive impact if they haven’t already made a decision on your application. So yes, there is—as with all of this, there are elements of nuance, there are elements of judgment.

Sam: I’ll add one more piece of nuance. At Harvard Law School, next to impossible to be admitted with an LSAT score of a 155 or below. I’ll be super transparent about that. The people who were being admitted with scores around that range, or even a little bit higher, from like a 155 to a 160, were really superlative applicants, right? They had really extensive or substantial work experience that was very interesting and compelling and would’ve added a really important perspective to the class. They were people who had glowing letters of recommendation, and when I say glowing, like they could not have been stronger. These are people who just nailed it academically in their undergraduate or master’s program, so they were top of their class. And they had really compelling, clear, concise essays, right? So to get admitted with a score that’s that much below the 25th percentile, the rest of your app really needs to pack a punch and just be top-notch. There has to be something special about your app that you’re going to be adding significant enough value to overlook that lower score. So keep that in mind too. I think that’s important context when you’re looking at the range of scores and kind of who’s getting in with those.

[31:50] Anna: Okay, so let’s talk about the actual application review process. Because this is something that, to some extent, is a black box for applicants, and that makes sense. Why would you spend whatever valuable face time you have with applicants talking about your logistics and administrative systems and things like that? But can you both tell us a little bit about the actual application review process?

Julia: So, at Vanderbilt, we actually did not always review applications in the order we received them. And I think that’s a common misconception when people hear the term “rolling admissions,” they think that you get an application, you immediately read it, you immediately give a decision, and that’s not at all how it works.

At Vanderbilt, there was a little bit of a prioritization of certain applications. That could be for a number of reasons. Sometimes it’s because of the LSAT score, sometimes it’s because of the GPA, it could be because of where they went to undergrad, maybe they served in the military, that sort of thing. There were apps that were put at the front of the line. After that, we did go in chronological order, but it was certainly not a, you get an application in, you read it, you give a decision. It’s a much more complex and layered process than that.

Sam: Definitely. Harvard’s process was a little bit different. We, in most cases, read apps as they came in. We typically tried to read them in the order they were received. Distribution of those files was random between all the readers on the team. Except at the very end of the cycle or except before interview cutoff dates. So if we were approaching, like, an interview invitation for our last committee or before our first committee or something like that, we might sort applications by LSAT score, by GPA, maybe by certain populations like military or first gen, Pell Grant eligible, applicants with tribal affiliation, and prioritize those apps just to finalize our interview selection process before we had to move on to the next committee or our final committee.

Julia: And that reminds me of something that came up when Sam and I were preparing for today, which is that, at Harvard, you hear a lot about this “committee.” At Vanderbilt, there actually wasn’t a committee. You know, you see it all the time, I see it all the time on Reddit, people talking about the admissions committee. And just note that at some schools, there really isn’t a committee. It’s really individual admissions officers reading applications and then ultimately coming to a decision that takes everyone’s opinions into account. But it’s not always some conference room with a bunch of admissions officers sitting around talking about applications.

Sam: We definitely had a very traditional committee structure for admit decisions, for sure. And then we also had smaller committees for interview selection; we had committees for deny decisions; we had committees for waitlist decisions. So Harvard’s kind of unique in that regard. There was always, I would say, a minimum of two to three people making decisions in a committee setting. There was never one person making a final decision or final call. Dean Kristi Jobson is not the final or only say on someone being admitted. She really does take into account the perspectives of other people on her team, which I thought was really awesome.

Anna: Yeah, and law schools do very much vary in this. I will say, I have certainly not compiled all the data for every single law school or anything of that nature, but we have done consulting engagements, and we have worked with the admissions offices at many, many law schools. I personally have worked with, I believe, over 35. And it is more common to not have the sort of traditional “committee” where people are sitting around a table and discussing applications. It’s also not one person is just reading an application and making a decision, but it might be, you know, one person reads independently, and then they give it some sort of score or they give it some sort of recommendation—you know, “I recommend admitting this person,” or “I recommend waitlisting this person”—and then it goes to someone else, and they read that prior person’s notes, and they take those into account when they read the application. And then, you know, maybe it goes to the dean of admissions who takes those both into account in terms of their notes and recommendations, but they’re the one who makes the final decision.

These processes very much do vary from school to school. I would guess that it’s more common not to have an actual “committee” committee, but you know, you’re Harvard Law School, so we’ve all seen what your admissions process looks like in Legally Blonde. So there you go.

Sam: Yeah, exactly. That’s exactly what it looks like.

Anna: Precisely like that.

Sam: Bunch of white men watching videos, making decisions.

[36:07] Anna: Oh goodness gracious.

So you take this reading process, which may be to some extent it is ordered by the date that it was submitted. Maybe that ends up being kind of haywire based on various different circumstances. And then you add the dimension of when decisions are released, and oftentimes things just feel completely outside of the realm of understanding from an applicant who’s on the outside—”I submitted my application four months before this person. How are they receiving a decision before me?”—and none of it makes any sense. And there are a lot of factors that go into this. And they are very school-specific. Any dimensions of nuance to add to that quagmire or that enigma?

Julia: Yeah, sometimes, you know, we’re prioritizing certain apps; others are going to have to wait. Sometimes, it’s just logistically we have to get through thousands of apps. So your application, it’s not that we’re putting it off or we’re not trying to give you a decision. Admissions officers really do have a lot of work to do and a lot of files to read. So I just always like to remind applicants that, don’t take it personally, don’t think it’s a reflection of your application. It might just literally be that you are #2,000 in line to get read.

Sam: I’ll say at Harvard Law School, the reason people ended up waiting to get decisions, at least with our process, was we would often review an app a couple times, and there would be really good potential there, but we weren’t quite ready to admit that person or send them to our interview pool. We needed to wait on that person and see more of the pool over a few more months to see how they stacked up when final applications were rolling in. So sometimes we used to put people in the “hold” bin, is what we called it. They were stuck in a holding pattern. As more apps came in, we would pull up former apps that we’d already reviewed that we had thought had good potential, and we would compare them to the whole pool at that point and say, “Oh, actually, this person is even more competitive than we thought. We’re going to bump them up to interview selection,” or, “After seeing the rest of the pool, this person just doesn’t quite stack up, so we’re now going to move them to deny.”

So that’s sometimes the reason it took a while for some people to get decisions. But I always used to say, “If you haven’t heard from us, that’s always a good thing, because that means we’re still actively considering your application and we saw good potential there. So just hold tight. It could mean really good stuff for you. It doesn’t mean that we’re taking longer that we don’t like your application or we’re not prioritizing it. We’re just trying to see how it compares to the rest of the pool.”

Anna: Sam, that’s a great point on some applications being held up because admissions offices want to see how the rest of the applicant pool ends up shaping up. That’s another component of the rolling admissions process, is that you are going to continue to get great applications in January, February, March, and you’re not necessarily going to have a great idea of what the applicant pool as a whole is looking like at the point that you start reviewing those first applications.

And Julia, I think your point is even more salient this particular cycle when we are looking at a significant increase in applicant numbers over a year that was already itself a significant increase in applicant numbers and at a point where a lot of institutions of higher education are facing issues with bringing on new staff, and maybe having things like hiring freezes and having issues with bringing in people. So at some schools, you’re going to have teams that have the same number of people that they had two years ago, but drastically more work for each of those people, drastically more applications for each of those people to read.

Sam: Yes.

Anna: And that does take a lot of time. Admissions officers do want to give every application a fair shot and really be able to review them. So things may take a while. We’ll see; we’ll see.

[39:32] Sam: Definitely. It’s going to take a while this cycle. But hold tight. It doesn’t mean bad news.

The other thing we quickly wanted to touch on is the order in which apps are reviewed, because sometimes that can differ from school to school, But I think generally speaking, schools tend to start with the application form that you fill out and submit through the LSAC. Admissions officers then tend to look at the CAS report that LSAC generates for you that has your LSAT score history, it has your GPA, and how that compares to other people applying to law school from your same undergraduate institution. The CAS report has tons of helpful information that admissions officers will really look through and consider. They then typically look at your resume and your work experience, your extracurricular activities, what you’ve done with your time, both during undergrad and beyond. If you’ve graduated, they’ll look at your transcripts and go through those line by line and look at the classes you’re taking, look at the grades that you received in them. They’ll read all of your letters of recommendation. They’ll then read your statements. Statements are typically one of the last things that are read, interestingly enough. And then the addendum. Any additional addenda, optional addenda are typically read last, so that’s usually the order. Julia, any differences on your end, or Anna, when you read?

Julia: I did it a little different, actually. I would start with the application form. Then I would usually—and I’m not speaking for everyone at Vanderbilt, I’m sure—but I would read the application form just to get a general sense of where you’re coming from. I would then actually usually skip to the resume. I think it’s like a really quick snapshot of just your background, your experience. Then I would usually read statements after that. And then I think it could have been just how it was organized for us. But then I would go and look at the CAS report, including letters of rec and that sort of thing. This wasn’t always the case. Sometimes, you know, I would start out reading and then see something in the application form that made me curious. So I might skip to another part of the application to look further into it. But it’s definitely interesting how it varies from school to school. So I guess all of this is to say that don’t assume that everything is the same at every law school. We all definitely do things differently.

Anna: So now I’m a little embarrassed to say that I would typically look at the CAS report first, which now makes me feel like oh, I was too focused on the numbers—which, you know, I don’t think is particularly the case; I don’t think that the specific order in which you read an application means all that much in terms of the overall ethos of the admissions office. But just to say that there is even more variation. It can be in different orders.

Most applications are probably read, in terms of when you’re looking at the statements, in the order that you see your, like, application PDF preview essays. The reason that I’m bringing this up is because I think a lot of this that we’re talking about is a curiosity sort of thing. Like, here’s insight into how admissions offices work. One area where this can be relevant, I think, in terms of strategy—and something that we were talking about on our team relatively recently—is that if you submit an addendum, usually that’s going to be at the end of your application. So we were talking about this in the context of, okay, if a school gives you a little spot in the application form to talk about your C&F or you can submit an addendum, it’s advantageous to some degree to be able to put it in that application form, because then the last thing the admissions officer is reading isn’t your explanation of your character and fitness addendum of your underage drinking or whatever; that’s just earlier, that’s in the middle of your application, and they can end on a statement that you’ve written that talks about your strengths and positive things about your application. So that’s one component where I think it can be relevant to strategy.

Sam: Definitely.

[42:50] Anna: So, as we’re talking about my embarrassment with feeling like I was too numbers-focused with the CAS report, I think this is an interesting time to talk about the notion of “holistic review” generally. When I first started at Spivey Consulting, Mike actually did not like using the word “holistic” at all. He thought it was overused. He thought it was used to the point by admissions officers that it had started to, like, lose all meaning. And he’s actually come around on that since then. And I do think to some degree, things have had to get more holistic because schools just have many more people with the numbers that they need to choose from. So what else is there to look at? This is how Dean Blazer talked about it on our podcast when she was on earlier this year. How else are you going to make decisions? You’re not making them randomly. If you have more people than you need who have the numbers, then nothing else to look at but the rest of the application. Julia, do you want to talk a little bit about holistic review generally?

Julia: I think that holistic review is a term that is very misunderstood by applicants. And I see this play out in a few different ways. On the one hand, there are people who think that schools don’t do holistic review because, if you don’t have the numbers, you’re not going to get in, or if you do have the numbers, you’re definitely going to get in. And neither of those are absolute truths. On the other hand, you have people who think that holistic review means that you can apply with scores that are below both medians, but because you have a great application, other than your numbers, you have a good shot of getting in.

I just like to remind applicants that schools are reviewing your application holistically, but you really have to think of the numbers as a threshold you have to cross in order to really get that holistic attention to your application. So, if you have the LSAT score, you have the GPA, that’s really when that holistic review kicks in.

Sam: Definitely. What I’ve been telling my clients is, especially in a year like last year, in a cycle like this year where application volume is up so substantially, you know, at a school like Harvard, we had so many applicants who could do the work at Harvard Law School, that then the question became in our process, you know, what if we get, if we admit this person versus all these other people who’ve proven they’re equally as capable? And that’s where the holistic piece comes in. That’s where your statements can really make a difference. That’s where your letters of recommendation can give you a special kind of tip in the process. That’s where your resume and your work experience really matters. There are always going to be more people that can do well at a school than we have spots for. So that’s where these other components really matter.

I used to say—when I used to travel around the country and host recruitment sessions for Harvard, I used to say—every single year I have seen people with a 180 on the LSAT and a 4.0, I’ve seen several of those people get denied from Harvard Law School because the other application components just didn’t hold up to their numbers. So it really goes to show, it is so much more about the numbers. It really is a holistic process, and you really have to care about every single application component.

Julia: Yeah, I totally agree. I’ve seen similar things at Vanderbilt as well, where, by the numbers there’s an applicant who you would think is a slam dunk, and for whatever reason—they lacked work experience; we could tell that they just didn’t put any time or effort into their statements, that sort of thing—they would end up maybe not denied, but on the waitlist for sure. You know, that’s where you really see that holistic review coming into play.

[46:13] Anna: One thing I’ll note as we’re talking about things like thresholds and earlier talking about cutoff scores—we’re talking about these things in vague terms right now, and that’s because there is no real way to get more precise. There are these thresholds, but that is in and of itself sort of its own little mini-holistic review.

Julia: Yeah.

Anna: It’s not that your admissions dean is telling you, “Okay, anybody below this certain score is not going to get in.”

Sam: Right.

Anna: Or, “If someone is below this certain whatever it is, then don’t consider them.” It’s not that. And it is, even within that, trying to understand the person and where they’re coming from. You might see someone who has a score that is lower than you would normally consider, but they were valedictorian and president of their class in college, and they went to an amazing school, and they had an aerospace engineering degree or whatever; I am making things up. But there are, even within sort of this determination of, “Do they have the scores to be strongly considered for admission?” that is not like a black-and-white thing. That is not, there’s this specific threshold, and below you’re not going to get a shot.

And then the other thing is that people will often go in, when they are thinking of applying to a school where they are well below the stats, and they’re thinking about, “Okay, but I have all these other strong components in my application, so I’m going to be strongly considered.” When that is not the case, it is usually because the school, as we were talking about earlier, they want everyone who attends to be able to succeed academically. Sam, Julia, do you want to speak more to that?

[47:36] Sam: Yeah, so when we were prepping for this podcast, we were discussing kind of the categories for evaluation that applicants are going to be assessed on, that I think generally speaking are pretty true across law schools that you apply to.

And the first, Anna, that you’ve been talking about is academic potential, right? The #1 question admissions officers are asking when they’re reviewing a file for the first time is, “Will this applicant thrive academically at our institution?” And that’s demonstrated by many parts of the application. I think, chief among them is your LSAT score, your GPA, your transcripts, and the actual courses you took and the grades that you got. What was your major? Then your letters of recommendation can actually do a lot towards providing evidence for your academic potential. Your essays can as well in terms of how well they’re written and how well you’re able to convey ideas concisely and clearly.

Second, kind of, category that I think is true across the board is professional potential. Admissions officers are evaluating whether you are someone who’s going to be able to secure a summer internship, whether you are someone who’s going to be able to get full-time work after graduating. Are you someone that we can put in front of a potential employer and you’re going to represent yourself well, and you’re going to represent the school well? Because schools really care about their brand, and they care who they’re putting in front of employers, because that’s going to give employers confidence in hiring from that school in the future, right? Your professional potential is demonstrated primarily by your resume and the experiences that you’ve had professionally, but it’s also demonstrated through your letters of recommendation. Especially if there’s one written by someone who has managed or supervised you, that can provide a lot of evidence of professional potential. And then schools interview mainly for this purpose, right? To assess your professional potential, to assess whether or not you’re going to be able to interview with employers, whether you’re going to be able to work with a career office and be productive in terms of getting your resume and your interview skills where they need to be to get a job.

Julia: I think that category in particular is something we all have seen, in the past few years, has really become a priority at schools.

Sam: Yeah.

Julia: You know, I know in my three years at Vanderbilt, from the time I started until I left, the emphasis on interviews in particular really increased, and we went from interviews truly being optional—and not really having an impact, you know, if you didn’t do one, on your chances of admission—to, they were borderline required. We really wanted to try to get some face time with everyone we were going to admit, because we wanted to make sure that, when they get in front of a law firm or whoever they’re interviewing with, they’re going to be able to present themselves well and be successful in their job search.

[50:17] Sam: 100%. And more and more schools are starting to interview. There’s a couple that this year are interviewing all applicants, for the first time, that they want to admit, or that are giving applicants the option for the first time, which is exciting and kind of different.

Moving on to those categories. There’s a couple more that you’re going to be evaluated on. The next one is your fit for law school and the legal profession. This is one where, when I was an admissions officer, I actually saw probably the most applicants fail at providing evidence for. You need to make sure that in your application, you’re conveying your motivation for going to law school and what you want to do with a JD that you can’t do with just your undergraduate degree or a different degree, right? You really need to justify why you want to take up a spot at a law school to get this specific degree, and that’s evaluated by your resume, right? What experiences have you chosen to do professionally or through summer internships or extracurricular activities? Definitely demonstrated in your essay, and in fact, your personal statement, your statement of purpose should address this topic. If an admissions officer gets the end of your personal statement and they cannot identify why you want to go to law school or what you’re hoping to do with a JD, it’s going to be hard to get admitted anywhere.

And then the last sort of category is cultural fit or your interest in a particular law school. So does this applicant seem like a good fit for our school’s culture and environment? Do they seem genuinely interested and invested in attending if we admit them? Do we have offerings here, through courses, clinics, extracurricular activities that align with their specific stated interests and goals? So that’s something you’re going to be evaluated on, too, right? And you need to make sure you’re providing evidence for that. You can do it through essays, especially if you’re writing a “Why X” essay about why you want to attend a specific school. That can be demonstrated through your resume and the things that you’ve chosen to do with your time that might give admissions offices a clue as to what you’ll do in their law school environment and whether they have opportunities that align with what you’ve presented yourself as being interested in. And that can certainly be demonstrated through your letters of recommendation as well.

So those are sort of categories that you’re going to be evaluated on. They’re all important. But certainly, if you don’t pass one or more of those criteria, it’s going to be difficult to be admitted to some of the schools that you’re applying to. So you really need to think through whether you’re getting those things across in your application.

[52:40] Anna: Yeah, definitely. One thing I’ll note is that your interest in a specific school—which is separate to some degree, in some situations, from the notion of you’re fit at a school, but specifically, how likely you are to attend that school if admitted—is something that varies quite a bit in its importance from school to school. Some schools care a whole lot less, some schools really, really care quite a bit. So this is something where, if you err on the side of, you know, showing your strong interest in that law school, and as we were talking about before with researching “Why X” essays, finding those genuine factors that do make you really interested in the school, that’s going to be helpful for you, or at minimum is not going to hurt you. Certainly, in an interview question, if they ask you about your interest in the school, do not say anything negative about the school.

Sam: I will add the caveat that, like, at Harvard Law School, for example, we don’t ask for a “Why X” essay, or we didn’t when I was there, we didn’t really care. That being said, we were a school that didn’t have to worry about yield so much. There are schools that, you know, if you have super high stats, for example, and you don’t write the “Why X” essay that they give you the option to write, they might pass on you, or they might choose to admit other people over you, because they might be assuming that you’ll have other offers and that you’re more interested in potentially higher-ranked schools. So I do think it’s really important if there is a school out there that’s your top choice and you’re well above the medians, it really is in your best interest to make that clear through your application components or in your interview that that school really is your top choice and you would enroll immediately if admitted, because there are some schools who are trying to assess yield risk, and they don’t want to waste a ton of spots on people who they feel there’s no chance of getting them at that school that they’re not actually interested in coming.

[54:21] Anna: So one thing that I think admissions officers don’t love talking about is things that could get you denied really quickly. Because it’s not fun to tell someone, you know, “Oh, if you make this one mistake, you’re just out the door.” But those things do exist. One that Dean Blazer has talked about on our podcast is using the wrong school name. That’s never a good one. It’s not necessarily an auto-deny in all cases, but sometimes it is.

Sam, do you want to touch on a few other ones that are possible quick denials?

Sam: Happy to. So, a couple I’ve seen over the years are spelling and grammatical issues can really, really hurt you. One specific example that I will never forget from my time at HLS is, we had an applicant who spelled Phi Beta Kappa wrong, and we just could not move past it. Right? Because we were like, “Ah, this person, someone who was admitted to this really prestigious honor society, and they couldn’t even spell the Honor Society name,” right? So that really dinged that person.

A lot of people also just don’t follow application instructions, like they’ll go over the requested or suggested page length, even if you’re going over by one or two sentences, it just comes across as really sloppy, and that you don’t have an attention to detail, which is so integral to being a lawyer. People would submit essays that weren’t double-spaced, for example, or they were in like size 10 font, and you were like, “Ah, this is exactly what we told you not to do.” A lot of people at Harvard that just didn’t respond to our prompts, too. I remember getting essays, even last year, responding to prompts that were not our prompts, but we knew that they were other schools’ prompts. And so we were like, “Well, they were a little bit lazy, and instead of writing a new essay for us, they just submitted the same essay for this other school with a very different prompt,” which was never a good look.

I know I’ve mentioned this in my other podcast, but oversharing. You know, if you’re shocking, traumatizing, or disgusting an admissions officer at the beginning of your essay, that is all they’re going to be able to think about for the rest of your application, and it’s really going to color their evaluation of you. So just use your best professional judgment.

[56:05] Anna: Thank you for that, Sam. That is helpful, because that is one component that admissions officers aren’t necessarily going to be talking about.

Okay. So we have gone so long, we’re going to try to sort of run through the other big ones on our list of things that admissions officers really just they aren’t going to want to be talking about them; it won’t make sense for them to be talking about it, whatever it might be.

Julia, you have one on overcomplicating your materials. Can you speak a little bit to that?

Julia: Yeah, so this I see play out in a number of different ways. So with your resume, for example—and a resume is something that I feel very passionately about; it’s something that should be pretty simple—that people have a way of overcomplicating it. A lot of times, people will want to make their resume a different format. And really, the reason you want to avoid making your resume stand out by using an interesting font, that sort of thing, is that admissions officers will be giving your resume a very quick scan, and they’re used to seeing it in a very specific format. And if you deviate from that—and that’s not to say all resumes have to be exactly the same—but if you deviate from the standard resume format, you make it harder for them to read your resume and glean the information that you want them to take away from it. So you really just want to keep it simple. Make it easy to read, have it be well organized. We’ve talked on other podcasts about resumes and how long they should be, that sort of thing. But you really do want to keep them as simple and easy to read as possible. And that really goes for any component of your application.

Personal statements, for instance. You want those to be easy to follow. You don’t want to go in a weird order. One thing, when I was an admissions officer, that you know, I kind of groaned at when I saw it, was when someone tried to get overly philosophical in a personal statement. That’s not something that you can easily digest in a few minutes as you are reading an application. When I’m working with my clients, I frequently just tell them, “Your goal is to make this easy for an admissions officer to read.” You don’t want to be the applicant who they see your application and they just groan and dismiss it before they even have a chance to really get to know you as an applicant.

Sam: To that point, if you’re writing about an extremely esoteric topic, or writing something that’s very technical, or using a lot of big words that the average person or an admissions officer is not going to know, it might come across as arrogant. And it also is going to be really difficult, like Julia said, for the admissions officer to comprehend in one or two minutes. You’re going to lose them, it’s going to deter from the rest of your app.

[58:36] Anna: Yeah, I think the big component here that you’re probably not going to be hearing from someone who’s actively an admissions officer is that they might be moving really quickly through your application. And that might depend on certain circumstances; that might depend on all sorts of things; it might or might not have to do with you specifically. But chances are, if you make some of these mistakes that we’re talking about, if you make things more difficult for the admissions officer, they might start moving through it even more quickly, is how I will say it. So yes, definitely making everything really clear, making things conversational.

Our consultant, Derek, who was Dean of Admissions at the University of Pennsylvania [Law] for a number of years, he talks about how essays should be conversational. Not a conversation with, you know, your best friend, your college roommate; a conversation with a lawyer who’s in a position that you’re interested in, or with someone who is at a professional networking type of event. You want it to be something that is easily readable, easily understandable, so that an admissions officer can go through it relatively quickly and understand your most important points, understand what you’re trying to convey in a way that doesn’t require stopping and, like, really analyzing this one paragraph to try to understand, as like you were saying, Julia, like the philosophical point that you’re making, that kind of thing. That is something to prioritize.

The other component that we were talking about here is acting like you are a legal expert. So that’s separate from the notion of moving quickly through applications, but I think it’s also something that can be a little bit tricky to communicate to an applicant, especially if you are in a position of being an admissions officer. Julia or Sam, do you want to speak a little bit to that?

Julia: I’ll just say this as a former lawyer who ended up reading applications. These are applications that I definitely took note of, and not always in a positive way. I would definitely steer clear of getting into legal discussions, presenting an academic legal argument, that sort of thing. You’re telling us why you want to come to law school. You don’t want to make it seem like you think you already know everything. You want to tell us how our law school program is going to help you learn what you need to know to do what you want to do with your law degree. There are other people who aren’t lawyers who are reading applications, and you may lose them if you get too into the weeds talking about the law in your personal statement or whatever component of your application. So I’d try to steer clear of that, you know, to the extent you can. Obviously, you’re talking at least a little about the law in here, but you don’t want to get too detailed in that.

Anna: Yeah, I think your point about making a legal argument is a really good one, because if you are applying to law school, you’ve never been to law school, there are going to be some admissions officers, especially if they do have JDs, especially if they have practiced law, who might really peeved by you doing that, by you making this strong legal argument when you’ve never taken a law school class, when you haven’t been to law school, when you haven’t practiced law. So that is definitely a pet peeve of some admissions officers and not something you want to do.

Julia: And there’s also a lot of room for error there. You know, you could get something wrong, and then you have a whole different problem.

Anna: I think the other component here, in addition to making arguments, is making, like, grand statements about this is what the law is, making really strong and categorical statements about things that you haven’t necessarily learned about yet, because you haven’t been to law school.

[1:01:42] Sam: Or saying things in your personal statement like, “I will become a Supreme Court Justice.” I have definitely read those essays where I’m like—I just laugh because I’m like, “Okay, you know, that’s, like, going to happen to like 0.000001% of everyone who’s going to law school.” So to say those grandiose statements of these goals that you’re going to achieve, you don’t know if you’re going to achieve them. So you should always phrase them in a way that means like, “I aspire to,” “I hope to one day,” “If I’m lucky enough,” because you might not. And you just want to be cautious about coming across as overly confident.

Anna: That’s actually one I would expand to anytime you’re talking about attending a specific law school. So, like, in a “Why X” essay, much more subtle and much less of a, like, big red flag than saying, “I will become a Supreme Court justice,” but anytime you’re talking about attending a specific law school where you’re just applying, you haven’t been admitted, you haven’t decided that you’re going to go there yet, the opportunities you would take advantage of, the things you would like to do, it’s always a good idea to use words like “would,” “hope to,” “aspire to,” just in the way you were saying, Sam, there, as opposed to, “At X law school, I will do X, Y, Z,” because it’s presumptuous. You know, you don’t know if you’re going to get admitted to that law school. And if you are admitted, they don’t know if you’re going to come. So definitely, that’s one component that is important to remember. And yeah, that these various things can come across as arrogant, which is not how you want to be coming across in your law school application.

Okay. We wanted to briefly touch on interviews. Julia, I think you had another game for this one.

[1:03:16] Julia: We do. Never Have I Ever.

So, the first one is, never have I ever been able to answer a very niche or specific question about a clinic or a faculty member at the end of an interview. This was a personal pet peeve of mine. A lot of applicants do this because they want to impress their interviewer and show them that they’ve done their research, and there’s something about this school that they are really interested in. This plan usually backfires. You have to remember that admissions officers work in admissions. We are reading applications. We know about the school, but we don’t know all the details. We don’t run the clinics; we’re not faculty members; that sort of thing. And it puts the admissions officer in an awkward position of not being able to answer your question. When you’re thinking of questions to ask at the end of the interview, remember who you’re asking. Obviously, if you’re interviewing with a faculty member or something like that, they may be able to answer questions admissions officers can’t. But just keep this in mind when you’re thinking of what questions to ask and who’s going to be answering them.

Anna: Yeah. Definitely, definitely. I think keeping in mind the admissions officer’s level of knowledge is a good idea generally. I remember thinking exactly this when I read the advice online of, don’t ask something that can be easily answered by looking at the law school’s website. So I was like, “Okay, so I have to find something, like, hyper-specific that this information, like, doesn’t exist anywhere online because it is like this very niche thing.” And at that time, I was working with Mike and Karen, with Mike Spivey and Karen Buttenbaum from our firm, and they were like, “No, no, no, no. That’s not the direction that you need to go in.”